Navigation

Coralpedia Established to Identify Corals, Soft Corals and Sponges of the Caribbean

Professor Charles Sheppard of the University of Warwick, UK, responded to what he perceived as the need to have a good, comprehensive source of identification for the main reef occupiers and builders of Caribbean reefs, namely corals, soft corals and sponges by developing Coralpedia.

|

| Montastraea franksi (Gregory 1895) Large massive colonies, with irregular and lumpy surfaces. Colouration is basically orange-brown with many pale patches on the lumpy surface, but may be grey or greenish-brown. This species mostly grows in the open like other species of this genus but smaller, encrusting colonies are common in shaded overhangs. (Note diver in background to give an idea of the size.) |

Professor Charles Sheppard of the University of Warwick, UK, responded to what he perceived as the need to have a good, comprehensive source of identification for the main reef occupiers and builders of Caribbean reefs, namely corals, soft corals and sponges by developing Coralpedia.

|

| Acropora cervicornis (Lamarck 1816) This coral is now uncommon, though it is probably the most common of the two 'staghorn' corals in many parts of the Caribbean region. Branches can be over 1 m long and are slender, and colonies are usually loosely packed or ‘open’. Branches are round in cross-section, and sub-branches emerge nearly at right angles. The colony as a whole is much more open and loosely packed than Acropora prolifera, with which it may be mistaken. |

When asked why he developed Coralpedia, he said that there was a need for a more comprehensive identification source, showing the wide range of forms which many species can show, given the popularity of the Caribbean as an area for research, especially of the kind which uses countless ‘amateur’ divers for data gathering.

Furthermore, he added, “Some popular books have many errors, and are incomplete. Most of the detailed taxonomic literature is obscure and of little help to field work.”

|

| Acropora cervicornis |

“At present, many reef surveys are being done throughout the Caribbean region, and have been done recently. Most record several species by name, but almost all leave many important reef components as e.g. Sponge 1, 2 or 3 or soft corals A, B, C… etc. Someone working in, say the British Virgin Islands (BVI) cannot therefore assume his or her Soft Coral 6 is the same as the Cayman Island survey’s Soft Coral 6. Indeed, it probably isn’t the same. Thus no cross-regional comparisons can be made."

|

| Acropora palmata (Lamarck 1816) An unmistakable coral, commonly called Elkhorn. Branches can be over 2 metres long and as thick as a human body at their bases. |

The Coralpedia site has a fascinating array of photographs of corals arranged by taxa and by shape and each one is accompanied by notes.

The site invites ongoing discussions about the Most of the photographs were taken by Charles Sheppard or Anne Sheppard. Among the other contributing photographers are Douglas Fenner, Ernesto Weil, Joao Faria, Juan Sanchez, Pedro Rodrigues Frade, Sven Zea. Spanish translations are also available done by Dr Rodolfo Rioja-Nieto, University of Warwick, UK. The website was designed by Dan Neal.

Coralpedia was aimed at and paid for in part by The Overseas Territories Environment Programme, a United Kingdom development fund. (See note below.) Many of the illustrations were taken during another earlier OTEP-funded project connected with marine protected areas of the British Virgin Islands. Sheppard said it has “taken off very well.”

|

| Colpophyllia natans (Houttuyn 1772) This is a very large, meandroid or brain coral whose colones may exceed I metre across. Its valleys may extend the entire width of colonies, or be subdivided into shorter series. The valleys and walls are broad and may be 2 cm wide, which distinguishes this brain coral from the Diploria species which are narrower. Walls commonly have a groove running along their tops. There is a sharp break between the wall and the valley floor. |

The identification of species is an evolving process. Correct identification sometimes differed with other experts, in which case Shepard said he found a resolution, “which may of course change again later.”

Among those providing general comments and taxonomic advice which sheppards says is sometimes extensive advice, are Professor Nancy Knowlton, Dr Judy Lang, Dr Doug Fenner, Professor Ernesto Weil, Professor Sven Zea, Professor Rolf Bak, Dr Juan Armando Sánchez and Dr Emre Turak.

|

| Colpophyllia natans |

Feedback and expansion: A Call for Participation by Professor Sheppard

For many species, too few photographs exist of good enough quality.

|

| Diploria labyrinthiformis (Linnaeus 1758) A brain coral, unmistakable because of its 'double-valley' character. This double valley is a groove on the ridge called an ambulacra. |

For several, even in the relatively well studied Caribbean, none exist at all in the public domain (other than of perhaps a dried, blackened and shriveled remnant which no longer gives any hint of its once splendid living form).

Too often, web searches for a species yield only accounts that the species was found somewhere, by someone, with no (or poor) photo or description, offering a user a variable degree of confidence in its identification. This tries to fill that gap.

|

| Diploria labyrinthiformis |

Users are encouraged to send more illustrations, and are asked also to comment and correct any part of it. If you contribute, all you will get is the copyright of your own photos, and a warm feeling. But, with enough of that, this could become a useful resource for workers in the rapidly degrading marine environment of the Caribbean region. Please help! I view this as a work-in-progress, and hope a version 2 will be a marked improvement.

|

| Eusmilia fastigiata (Pallas 1766) Colonies are clumps of tubular corallites, each with one to three centres that are round to oval in shape. |

|

| Eusmilia fastigiata |

Note:

The Overseas Territories Environment Programme (OTEP) is a joint programme of the Department for International Development and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to support the implementation of the Environment Charters, and environmental management more generally, in the UK Overseas Territories.

The OTEP “has been established to support the Overseas Territories (OTs) in developing and implementing action plans under their respective Environment Charters signed jointly with HMG in September 2001. These Charters set out a range of policy objectives and undertakings….”

|

| Mycetophyllia aliciae (Wells 1973) Colonies are usually relatively thin plates, sometimes domed. They are meandroid, but in many colonies, their central parts have no clear valleys and ridges, but intsead individual corallites protrude a little. This especially occurs in deeper water. In others, the central parts loose all ridge formation, or there may be several polyps between ridges. |

The goal of OTEP is 'enhanced quality of life and livelihood opportunities for the inhabitants of all UK Overseas Territories through the sustainable use (or protection, where necessary) of environmental and natural resources, whilst securing global environmental benefits within the scope of the core principles of the relevant multilateral environmental agreements.'

It assists the OTs in taking ownership of and responsibility for the issues, by helping them to assess problems and to promote sustainable solutions to them through national strategic planning processes and action at the local level. OTEP provides a total of £1m per annum (£500,000 each from the FCO and DFID). The FCO component is a ring-fenced commitment from the Global Opportunities Fund (GOF).

|

| Mycetophyllia aliciae Three species. |

|

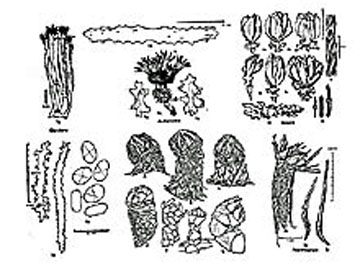

| All corals have skeletons made of calcium carbonate, the same material that composes sea shells. This diagram shows the various forms of coral skeletons. Image: NOAA |

The previous photographs are of corals. The following are of octocorals and of sponges.

Octocorals:

|

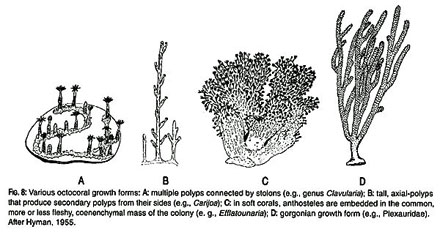

| Octocorals—the sea fans of tropical reefs—are classified within the Phylum Cnidaria and Class Anthozoa. All anthozoans are benthic, polyp-bearing corals and, unlike sea jellies and most hydroids, have no medusa stage. Each polyp on an octocoral (octo means eight) has eight hollow tentacles fringed with little branches called pinnules. This feature distinguishes octocorals from hard corals, which have simple tentacles in multiples of six. Octocoral colonies can grow in a variety of sizes and forms. Soft corals or sea fans often grow into large structures, while others are very small and develop by (A) spreading stolons (runners) on the surfaces of rocks. Others grow vertically with the first polyp at the top (B). Most, however, occur as large and sometimes massive, structures. These are commonly called soft corals (C) or sea fans (D). Image: NOAA |

|

| Coral colonies were often found and brought to the surface during some of the earliest explorations of the deep sea. Image: NOAA |

|

| Image NOAA |

|

| Pseudopterogorgia elisabethae Bayer 1961. This species is less than 1 metre tall. Its side branches may be pinnate (paired on opposite sides of the main branches) but often are not pinnate. It is moderately slimy, but not as much as is the case with P. americana. Photo by Juan Sanchez |

|

| Pseudopterogorgia elisabethae Bayer 1961. Photo by Juan Sanchez |

Sponges

|

| Barrel sponge pumping dyed water. Photo: Steve Gittings NOAA Sponges are composed of a number of different kinds of cells, connective structures, and water canals. Some cells, called choanocytes, line the canals and have hair-like structures called flagella. By moving the flagella, the cells allow water to sucked through tiny holes in the porous colony, into larger canals, and send it shooting out through large holes. It’s hard to see with the naked eye, but add some dye to the water surrounding the sponge and your senses are in for a feast! By studying the filtering rates of sponges, we will get a better idea of just how important they are to the water of the reef. Source NOAA "It's a Sponge, Bob!: Mission" |

|

| Aplysina fulva (Pallas 1776). A rope sponge, almost always yellow or yellow brown, forming tangled masses sometimes more than 1 metre across and high. |

|

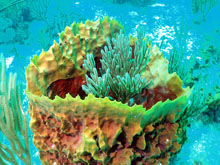

| Xestospongia muta (Schmidt 1870).n This forms very large barrels, usually solitary but sometimes in clumps of two or three. |

|

| Agelas tubulata Lehnert & Van Soest 1996. This forms clusters of tubes. The openings of the tubes are fairly broad and the end of the tubes are well rounded. Sometimes tubes may be fused to nearly half way up their lengths. Tube apertures may have a thin rim of a different colour. |

Photographs by Charles Sheppard or Anne Sheppard except where otherwise credited.

Contact:

Professor Charles Sheppard

Dept Biological Sciences

University of Warwick

Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK

charles.sheppard@warwick.ac.uk

Note: Re. Juan Sanchez, photographs.

Juan Armando Sanchez M., Ph.D. is Profesor Asociado and

Director - Laboratorio de Biologia Molecular Marina (BIOMMAR), Departamento Ciencias Biologicas-Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de los Andes

Bogota,COLOMBIA

Email: juansanc@uniandes.edu.co

Note: Please visit Horizon International's Magic Porthole coral reef coverage with video clips, exhibits, games and contests is at: http://www.magicporthole.org/

Magic Porthole Resources are http://magicporthole.org/resources.html

Search

Latest articles

Agriculture

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Air Pollution

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Biodiversity

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Desertification

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- UN Food Systems Summit Receives Over 1,200 Ideas to Help Meet Sustainable Development Goals

Endangered Species

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

- Coral Research in Palau offers a “Glimmer of Hope”

Energy

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Wildlife Preservation in Southeast Nova Scotia

Exhibits

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Coral Reefs

Forests

- NASA Satellites Reveal Major Shifts in Global Freshwater Updated June 2020

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Global Climate Change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

Global Health

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- More than 400 schoolgirls, family and teachers rescued from Afghanistan by small coalition

Industry

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Natural Disaster Relief

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

News and Special Reports

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

Oceans, Coral Reefs

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Pollution

- Zakaria Ouedraogo of Burkina Faso Produces Film “Nzoue Fiyen: Water Not Drinkable”

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Population

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Public Health

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Rivers

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Toxic Chemicals

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Actions to Prevent Polluted Drinking Water in the United States

Transportation

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Urbanization Provides Opportunities for Transition to a Green Economy, Says New Report

Waste Management

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water and Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution