Navigation

Lentil and Chickpea Production in Jordan

Food legume improvement project (FLIP) is under the rain-fed agricultural research program at National Center for Agricultural Research and Technology Transfer (NCARTT) in Jordan, a government body under the umbrella of the Ministry of Agriculture.

Location:

Countrywide, Jordan

Problem Overview:

Chickpea and lentil are considered major food legume crops in Jordan since they are an important part of the diet. However, production of these legumes declined in the last years. Originally an exporter of lentils and chickpeas, Jordan now (1986-1997) imports its major local requirements of chickpea and half of its requirement of lentil because of low yields and rising labor costs. Most farmers harvest lentil and chickpea using manual labor and become caught in a labor crunch at harvest. They are switching to other crops, such as onion, tobacco and cereals, to increase profits. Cereal growing is more mechanized.

Background:

In Jordan chickpea is mainly consumed as “Hummos beteheina”. Sometimes it is harvested and sold green at physiological maturity as “hamleh”. Lentil is consumed as soup or "Mjddara" , both of which serve as a popular dish and are rich in a relatively cheap source of protein. From 1986-1997, the average area in Jordan planted to chickpea was about 1560 ha and 3800 ha to lentil. During the same period, of its total consumption Jordan produced about 9 % of its chickpea and 50 % of its lentil.

In Jordan, chickpea and/or lentil rotate with cereals, mostly wheat, in rain-fed areas where annual rainfall usually exceeds 300mm. This is a semi-arid zone with annual precipitation of 350-500mm and with a total area of 135.9 thousand ha. In this zone the rainfall is characterized by high variability, irregularity and occasional high intensity. The temperature is moderate in winter and relatively hot in summer leading to low and high evapotranspiration in winter and summer, respectively.

To insure good reserves of soil moisture, control weeds, and avoid the occasional incidence of Aschochyta blight (ABL) disease, farmers usually grow lentil mostly in December and delay chickpea to spring, usually until March. However, spring sowing of chickpea is one of the main causes of the low productivity. The crop matures in a relatively short season and the effective rainy season usually ceases as early as March. Then, the plants are subjected to drought with low soil moisture, high evapotranspiration and heat stress with strong and hot winds called “Khamaseini”.

Traditional cultural practices, which are still used by certain farmers, add to the low productivity of the crops. Farmers might use the traditional cultural practices for different reasons, mainly to reduce the cost because they do not have the money, even though they are relatively aware of its usefulness. Some may not be adequately informed of the alternatives and are doubtful of their usefulness, or they may be concerned that they cannot get all the necessary inputs.

The traditional cultural practices are:

Tillage practices and seedbed preparation:

Some farmers are still using moldboard and the disk plow.

The recommendation is to use the chisel plow followed by duck-foot and rolling following planting in order to minimize soil erosion, conserve moisture, to level the soil and to push the stones in the soil.

Planting:

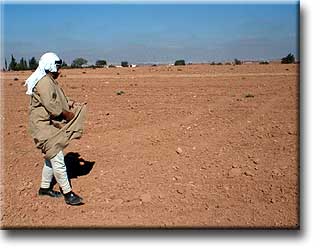

Many farmers are still using hand spreading followed by harrowing to cover the seeds instead of drilling. As a result, furrows are formed in the fields. This leads to no uniformity in seed distribution (variable plant density) and an unleveled field. Plants at the bottom of the furrow will receive more moisture compared to those in the top hill of the furrow. This will lead to no uniformity in maturity and create a difficult situation for any proposed mechanized harvest. Furthermore, some seeds might be buried deep down the soil so that germinated seedlings have little chance to reach above the soil surface, leading to low plant density.

Source of seeds:

Some farmers still use their own seeds or buy uncertified seeds from local markets for planting rather than the recommended and improved certified seeds.

Date of sowing:

Some farmers still delay lentil planting until late December or January. Chickpea is delayed until the end of February or March. They attributed this to their uncertainties about the rainy season and risk of weeds and Ascochyta blight on chickpea. These problems usually lead to low yield because of the short growing season.

The weed problem can be partially solved by planting following weed cultivation when the first effective rain allows weeds to grow. The use of chemical weed control later in the season is possible, or pre-emergence herbicide can be effective. Furthermore, improved varieties of chickpea resistant to Ascochyta blight are available.

Hand weeding is not always practiced due to labor cost and most of the farmers do not use pesticides or herbicides to control pests and weeds.

Whether it's worthwhile to weed or not is the decision of the farmer on the spot, and is based on his confidence in the field in respect to crop productivity and the rainy season.

Some farmers still do not fertilize mainly due to cost factors.

Some farmers buy seeds from the local market to grow chickpea and lentil without certified knowledge of the seed origin and agronomic characteristics. Some use their own selection from the local landrace, and others buy certified improved varieties from the Jordanian Agricultural Cooperative Establishment (JACE).

|

| a Jordanian farmhand spreading his seeds |

Farmers face the following obstacles in producing lentil and chickpea:

1. The small land tenure (more details will be presented later in the implementation). With small land holdings, many farmers are not able to economically adopt the recommended technology to grow these crops, such as seed drilling, soil leveling, weeding and mechanical harvesting.

2. The relatively low productivity. During the period from 1986 to1997, the average seed production of chickpea was 1100 kilograms per hectare (kg/ha) and lentil 800 kg/ha. This was partially due to the traditional cultural practices used. Furthermore, the highly variable and irregular rainfall prevailing during growing season in the Semi-arid zone usually lead to drought conditions that further reduced crop productivity and quality.

3. The high cost of production, mainly from hand harvest and weed control where labor cost is high especially at harvest. Mechanized harvest doesn’t offer the solution because it causes a relatively high seed loss during harvest especially for lentil. Furthermore, use of machinery is uneconomical for small land tenure situations (more details will be presented later in the implementation).

4. Market competition. As a result of low productivity, and the relative small seed size (specially for chickpea with varieties weighing 26-36 gm/100 seed), it’s not easy to farmers in Jordan to compete in their produce with that of other farmers in the neighboring countries such as Syria and Turkey whose crops are produced on a larger scale. There they use mechanization, have relatively more stable environmental conditions, and labor costs are lower.

|

| Lentil promising line, Rabba station, Southern Jordan |

Jordanian chickpea and lentil germplasm:

Following evaluation at the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), it was found that variation exists among Jordanian accessions of lentil for biological, seed yield and plant height. The evaluated Jordanian lentil accessions were among the earliest flowering and maturing accessions, and produced the highest biological and seed yields. Accessions tolerant to cold, iron deficiency or Fusarium wilt were found among Jordanian lentil germplasm. Considerable variation exists among chickpea accessions for seed yield and plant height. A large part (80%) of Jordanian accessions was Kabuli; 68% of semi-spreading growth habit and 92% with rough testa texture. The evaluated Jordanian chickpea accessions were susceptible to cold, Aschochyta blight and leaf miner. Lentil accessions from Jordan have been released or are in pre-release multiplication by national programs in Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Libya and Tunisia. The utilization of chickpea accessions is limited compared to lentil.

Food legume improvement project (FLIP) is under the rain-fed agricultural research program at National Center for Agricultural Research and Technology Transfer (NCARTT) in Jordan, a government body under the umbrella of the Ministry of Agriculture. The present project (FLIP) started after the completion of Food Legume Improvement and Mechanization Project (FLIMP) in 1992, which was a collaborative project between NCARTT, University of Jordan and the International Development Research Center (IDRC). Therefore, FLIP at NCARTT took over and continued the mission. Officially FLIP is responsible for conducting the research activities related to these crops. FLIP staff consists of the principal researcher (Nidal Nanish, two researchers and one researcher assistance.

NCARTT is a governmental center. It is considered a semi-autonomous body with administrative and financial independence. NCARTT consists of a national center located at Baqa' and six Regional Agricultural Service Centers. NCARTT is mandated to conduct and/or coordinate applied agricultural research and transfer of technology at the national level. Its mandate also provides for the identification, testing, transfer and adoption of improved technologies. FLIP is performing research mainly on chickpea and lentil under rain-fed conditions.

Food Legume Improvement Project at NCARTT has the following objectives:

1. To introduce, develop and produce chickpea and lentil varieties which possess the following characteristics:

1.1 High yielding: have large seed size, tall, erect, and resistant to pod shuttering and dehiscence and early uniform maturity (to avoid late season drought and heat stress).

1.2 Tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses:

Biotic; e.g., Aschochyta blight (ABL) on chickpea, Sitona weevil on lentil. Abiotic stress such as drought and heat.

1.3. Stable and adapted to the prevailing climatic conditions of the Mediterranean, where food legumes are usually grown in rain-fed area of the Semiarid-zone.

2. Maintenance of Basic seeds: through an established program the physical and genetic purity of breeder basic seeds of the certified varieties of chickpea and lentil are maintained.

3. To improve, develop and introduce the proper and optimum cultural practices suitable for production in the local rain-fed ecology of food legume in Jordan, including using the chisel plow and sweep to prepare seedbeds, the grain drill for seeding and fertilizing, and the roller. Make recommendations for equipment adapted to specific terrains used for mechanical harvesting, including a tractor back-mounting cutter bar (single or double knife), a self-propelled cutter bar, a plant puller, a grain combine, and a whole harvester. The most promising technique developed to date for improving chickpea production has been a modified, conventional grain combine used at a slower speed. For lentils, pulling and swathing, techniques are still being investigated to reduce straw loss, which is valuable for animal feed. Techniques and machinery are adapted to local conditions and socioeconomic factors.

4. Encourage farmers to adopt the recommended cultural practices through conducting on-farm yield trials.

|

Methodology:

FLIP staff at NCARTT are the principal people involved. Usually three farms are chosen annually to cover geographically the rain-fed production area of chickpea and lentil in Jordan. On-farm yield trail and field days (farmers invited) are conducted on these farms as a means of technology transfer mainly to introduce farmers to the new promising lines. Segregated population nurseries of chickpea and lentil are brought from ICARDA (F3/F4 generations). This is followed by single plant selection until the material reaches genetic purity and stability (usually F6/F7 nurseries). The selected elite lines are promoted to preliminary yield trials (elite and resistant material from biotic and abiotic stress nurseries are included here), followed by advanced yield trials, promising lines trials and on-farm yield trials and finally, the submission of varieties for release. Following release, the new varieties are placed together with the other certified varieties in a seed maintenance and multiplication process, where genetic and physical purity are maintained. The output of seed maintenance is handed to the production department in the Ministry of Agriculture for further seed multiplication. Then, it is handed to JACE, which is the official body responsible for selling the farmers the certified seeds for planting. Therefore, we conclude that our project has a ladder-like breeding system, which would consist of about four segregating population nurseries, yield trials, promising variety trials, and three on-farm yield trials for each crop.

Site: FLIP at NCARTT conducts its activities at three Regional Centers:

1. Ramtha regional center-Maru station (85 km Northwest of Amman, 520 m altitude, latitude 32° 33- North, longitude 35° 51- East) with annual average rainfall of 400mm.

2. Mshuger regional center (28 km Southwest of Amman, altitude 800 m, latitude 31°43- North, longitude 35° 48- East) with an annual average rainfall of 360 mm.

3. Rabba regional center (100 km Southwest of Amman, altitude 920 m, latitude 31° 16- North, longitude 35° 45- East) with an annual average rainfall of 340 mm.

Food Legume Project cooperates with ICARDA in performing nurseries and yield trials and exchanging information. Jordanian accessions of chickpea and lentil are kept at ICARDA germplasm bank. However, a germplasm bank has recently been established at NCARTT. Training and exchange of scientific visits is also another feature of cooperation with ICARDA.

Implementation:

The applicability throughout Jordan and in the other countries:

The results achieved and recommendations released either through present project or through the previous collaborative project are theoretically applicable. Nowadays, certain factors beyond the significant control of the farmers as well as the researcher contribute negatively to the applicability of the new recommended technology:

1. Farmer financial capability: high cost of production mainly from hand harvest.

Until now, research does not offer the optimum means of mechanical harvest, especially in small size land tenure. Furthermore, the cost resulting from production inputs such as, drilling and leveling, weed and pest control, and fertilization is relatively high. While farmer's financial capability is limited (details are discussed later in the cost factor). On the other side, the risk of crop failure resulting from drought worsens the situation.

2. Open market competition: nowadays the government policy has changed.

In the past the government was backing the prices in favor of the farmers by offering them a buying price for their produce higher than that of market. Therefore, compared to previous situation, one should expect that things would change concerning the ability of farmers to compete with market prices. After some time, socioeconomic studies have to be conducted to see how things changed since the previous studies concluded in 1992 by the previous collaborative project. However, in the absence of a direct government interference with prices in favor of the farmer, farmers may not be always able to compete with the sale prices of neighboring countries' produce.

3. Size of land tenure, the size of agricultural holding in Jordan (tenure) declined. According to 1997 Census (Table 1), the average size of the agricultural holding except the Jordan valley (an irrigated area) was about 3.9 ha (obtained by dividing the total area of holdings by the total no. of holdings) Table 1. 79.2% of the total number of agricultural holdings were in the holding interval 1-4.0 ha, comprising a total area of 61060 ha, this area equal to 21.9% of the total area of holdings. 56.5% of the total area of holdings was in the holding interval 5-100 ha; this comprises 16.8% of the total number of holdings. Only 17.4% of the total area was in the holding interval 100 to >200 ha, comprising 0.3% of the total number of holdings. Further decline is expected. In general, the above-mentioned size of land tenure and the expected decline do not encourage, economically, the use of mechanized production.

Table (1)

The distribution of agricultural holdings (tenure) in hectare in Jordan, except Jordan Valley for 1997.

Agricultural holdings | No of holdings | * % | Area (ha) | # % |

0.1-0.2 | 6624 | 9.2 | 791.1 | 0.28 |

0.2-0.5 | 13583 | 18.8 | 3962.4 | 1.42 |

0.5-1.0 | 11012 | 15.3 | 7250.2 | 2.60 |

1.0-2.0 | 14317 | 19.8 | 18547.1 | 6.66 |

2.0-3.0 | 7416 | 10.3 | 16825.8 | 6.04 |

3.0-4.0 | 4208 | 5.8 | 13683.3 | 4.91 |

4.0-5.0 | 2787 | 3.9 | 11800.7 | 4.24 |

5.0-10.0 | 6532 | 9.1 | 41891.7 | 15.04 |

10.0-20.0 | 3291 | 4.6 | 41032.3 | 14.73 |

20.0-50.0 | 1778 | 2.5 | 48787.1 | 17.51 |

50.0-100.0 | 409 | 0.6 | 25734.0 | 9.24 |

100.0-200.0 | 151 | 0.2 | 18870.7 | 6.77 |

>200.0 | 54 | 0.1 | 29412.6 | 10.56 |

Total | 72162 | 100.0 | 278589.1 | 100.00 |

Source: General Results of the Agricultural Census. 1997. Department of Statistics. Jordan.

* % Out of the total no. of holdings

# % Out of the total area of holdings

4. Climatic condition:

Jordan enjoys Mediterranean climatic conditions characterized by highly variable and irregular rainfall.

The normal rainy season mostly extends over the period from November-March. However, in last few years, it seems that there is a tendency for a shift in rainfall commencement from November/December toward January limiting the rainy months to mostly three: January-March (an unfavorable time). As a result, it was noticed in the field that seeds sown in December delayed germination until February. This means that the length of the growing season is shortened from six or seven months to four months. Furthermore, the plants are usually subjected to drought in the last two months. What worsens the situation is that there is a general decline in the amount of the annual rainfall below the normal annual average (in the 1998/1999 season the decline reached a climax. In that season and in general only about 33% of the long term annual average rainfall had precipitated. This adversely affects crop productivity and results in high crop and economic losses. Is this a temporary or a permanent climatic phenomenon? It's not known.

5. Cost factors:

The socioeconomic studies (FLIMP, 1992) revealed that the majority of farmers do not use a seed drill in sowing and they do not use pesticides or herbicides. Less than half of them do not fertilize. The Department of Statistics estimation of average productivity of lentil and chickpea over the period 1986-1997 was 800kg/ha lentil and 1100 kg/ha chickpea. It is not, however, certain that these production figures resulted from certain production inputs (i.e., sowing using drill or hand sowing, fertilization or no fertilization, weeding or no weeding, etc.). Therefore, it is not possible to calculate the net return of lentil and chickpea based on these figures. However, if we assume that the minimum production input is used, as those in Table (2), the cost of production would be about 418 JDs/ha, for both lentil and chickpea. Based on 30% harvest index for both crops, to avoid money loss, the minimum seed and straw yield for lentil should be 522.8, 1218.2 kg/ha (based on prices of 1999: 450, 150JDs/tone for lentil seed and straw respectively). For chickpea, based on 1999 prices (500, 75JDs/tone, for seed and straw respectively), the minimum seed and straw yield should be 620.7, 1446.2 kg/ha.

Table (2)

Cost of production/ha of lentil and chickpea using minimum production inputs. In rain-fed areas of Jordan (average annual rainfall of 300-450mm)

Cost elements | Unit | Quantity | Value/JD | |

Production inputs * Seeds |

|

| Lentil | Chickpea |

(kg) | 120.0 | 52.0 | 63.0 | |

Fertilizer | (kg) | 100 | 20 | 20 |

Bags | (no.) | 10.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

Total |

|

| 79.0 | 90.0 |

|

|

| ||

Mechanized work Land preparation including harrowing to cover the seeds | (hr) | 3.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

Threshing | (hr) | 4.0 | 32.0 | 32.0 |

Sieving | Tone | # 0.8, 1.1 | 4.0 | 5.5 |

Transport | (Tone) | 0.8, 1.1 | 2.4 | 3.3 |

Total |

|

| 40.9 | 43.3 |

|

|

| ||

Labor work Hand sowing (spreading) | (hr) | 17 | 8.5 | 8.5 |

Fertilizer spreading | (hr) | 17 | 8.5 | 8.5 |

Weeding | (hr) | 100 | 75.0 | 75.0 |

Hand harvest | (hr) | 140,120 | 90 | 77.1 |

Straw racking packing, loading and unloading, others | (hr) | 14.0 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

Total |

| 189.5 | 169.0 | |

Interest (6.0%) |

| 18.6 | 18.1 | |

Land Rent |

| 200.0 | 200.0 | |

Grand total |

| 528.0 | 520.3 | |

* Based on the current (98/99) prices cost of the certified variety seeds of lentil and chickpea (432,522 JDs/tone) bought from Jordanian cooperative establishment (JACE)

# Productivity of lentil and chickpea/ ha.

However, from our experience in our project at NCARTT, a seed yield target for chickpea and lentil of 1500 and 1100 kg/ha (harvest index 30%) is not difficult to achieve when the recommended cultural practices are used with good management, under a relatively favorable rainy season, (Table (3)). The cost of production when the recommended cultural practices are to be used is 511.2, 512.3 JDs/ha for lentil and chickpea respectively (Table (3)). On the basis of this improved yield, the net return of lentil and chickpea could be 272.6, 493.4JDs/ha respectively (Table (4)).

Table (3)

Cost of production/ha of lentil and chickpea using the recommended practices. In rain-fed areas of Jordan (average annual rainfall of 300-450mm)

Cost elements | Unit | Quantity | Value/JD | |

Production inputs * Seeds | Lentil | Chickpea | ||

(kg) | 120.0 | 52.0 | 63.0 | |

Fertilizer | (kg) | 100.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

Herbicide | (L) | 1.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 |

Pesticide | (L) | 1.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

Bags | (no.) | 10.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

Total | 124.0 | 135.0 | ||

Mechanized work | ||||

(hr) | 1.7 | 18.9 | 18.9 | |

Seed drilling and fertilization | (hr) | 0.6 | 10.1 | 10.1 |

Spraying (herbicide and pesticide) | (hr) | 0.8 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

Threshing | (hr) | 4.0 | 32.0 | 32.0 |

Seed sieving and cleaning | tone | # 1100,1500 | 5.5 | 7.5 |

Transport | (Tone) | # 1100,1500 | 2.4 | 3.3 |

Total | 72.1 | 75.0 | ||

Labor work | ||||

(hr) | 140,120 | 90 | 77.1 | |

Straw racking packing, loading and unloading, others | (hr) | 14.0 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

Total | 293.6 | 97.5 | 83.6 | |

Interest (6.0%) | 17.6 | 17.7 | ||

Land Rent | 200.0 | 200.0 | ||

Grand total | 511.2 | 512.3 | ||

* Based on the current (98/99) prices, cost of the certified variety seeds of lentil and chickpea (432,522 JDs/ tone) bought from Jordanian Agricultural cooperative establishment (JACE)

# Productivity of lentil and chickpea/ha.

Table (4)

Expected revenue of chickpea and lentil JDs/ha, for both productions under common farmer and recommended practices. In rain-fed areas of Jordan (average annual rainfall of 300-450mm).

Crop | Cost of production JD/ha | Average biological yield (kg/ha) | Average seed yield (kg/ha) | Average straw yield (kg/ha) | **Total income JD/ha | Net return JD/ha |

Lentil | 528.0 (511.2) | # 2200 *(3025) | 800 (1100) | 1400 (1925) | 570.0 (783.8) | 42.0 (272.6) |

Chickpea | 520.3 (512.3) | 3600 (4909) | 1100 (1500) | 2500 (3409) | 737.5 (1005.7) | 217.2 (493.4) |

#: Yield under farmer’s common cultural practices.

*: Possible improved targeted yield under recommended practices (harvest index 30% for both crops).

**:Based on average current wholesale prices (1999), for the local produce of lentil and chickpea (450, 500 JDs/tone for seeds and 150, 75 JDs/tone for straw, respectively).

Some farmers do not calculate the cost of production properly. Most of farmers own their land and are not aware that they should consider land cost and interest in their balance. Therefore, when considering returns they do not include these in the cost (land, interest).

In general it can be noticed that labor cost, mainly from harvesting and weeding (70-100 JDs/ha for each process) contributes significantly to the high cost of production. Mower harvest (cutter-bar) of lentil and chickpea theoretically can reduce the cost of harvest down to 10.2 JDs/ha. But the main drawback is that, in most cases, the size of land tenure is small (Table (1)), for which mower harvest is not suitable. Furthermore, high seed losses of 10-15% or more arepossible and the extra cost to pay for seedbed preparation, land leveling and seed drilling makes farmers hesitant to use the recommended inputs. A farmer with limited financial capability under the current market prices for his produce tends to drop the use of costly inputs (i.e., soil leveling, seed drilling, weed and pest control, fertilization). Some farmers work collectively with their family members in weeding and hand harvest to reduce production cost. On the other side the sale prices for imported lentil and chickpea are relatively higher than that of local produce, due to seed cleanness and to the large seed size, especially for chickpea.

As a result, some farmers started to switch their land-use by growing tobacco/onion, or renting it for tobacco/onion growers especially in areas to the north of Jordan receiving relatively favorable rainfall (annual average >350mm). Tobacco is considered a soil-depleting crop, but in general, the net return of tobacco/onion is usually higher than that of legume. However, the area planted to tobacco is restricted and the size is determined each year by the understanding of the Tobacco Company and the government. Tobacco growers have to be licensed and have to make a contract with the company that will buy their produce.

Concerning farmer's social point of view, his work in his land means much to him. It means pride, dignity, respect and important source of time spending and employment (his job). Therefore, not every farmer likes to offer his land for rent, unless he is forced to when he suffers from economical difficulties beyond his tolerance. On the other hand, some farmers look to the situation from pure economic standpoint (profit), when they consider renting their land.

However, under the conditions of water scarcity and the continuous decline in the size of land holdings, which may reach far below 3.9 ha (a recent low has been enforced allowing the fragmentation of land holdings down to 0.4 ha in certain areas), we ask, "What we can do?" This we ask in terms of what are the most profitable crops to grow. What is the subsequent social impact in terms of farmer's income, cost, prices and employment?

However, certain things can be done to improve applicability of the recommended cultural practices including the activation of the role of extension services. This will strengthen the bridge between research and farmers. But this process should be comprehensive and continuous mainly through on-farm yield trials and connected field days. Farmers can also be reached through mass media, especially TV (extension programs), in addition to published pamphlets. Farmers may work collectively through associations and unions so that the cost of production inputs may be reduced. The Jordan Cooperative establishment rents the required equipment to farmers who request it. They also conduct demonstration trials on seeding and harvesting. Plowing, drilling, spraying tools and other equipment can be bought through these cooperative unions and hired by the participating farmers at non-profit prices. Furthermore, seeds, fertilizer, pesticides and herbicides can be bought wholesale and sold to farmers at a relatively cheaper price.

Replicability:

The results, findings and recommendations of the previous collaborative project together with those of our current research project in Jordan (FLIP), can be successfully applied in other countries given that the crops are grown under more stable and favorable environmental conditions. Fields size (land tenure) should be large enough to allow the economic use of mechanization in production.

Lentil and chickpea producers on rain-fed farms can use this methodology. It can be used by farmers with access to machinery as well as those with smaller farms or farms working on stony or hilly soils.

A similar program has been developed in Tunisia and the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomic de Tunisie, involving improved strains of lentils and chickpeas, seed production, and recommended agricultural practices.

What is the impact on nutrition?

An increase in the nutritional contribution of Lentil and chickpea might result from an increase in crop productivity, high protein concentration or improvement in protein quality. At present, our project is working toward increasing crop productivity. Increasing crop productivity means we are increasing land productivity of protein and at the same time farmer income is supposed to improve leading to a promotion in his welfare and well-being. This is if we consider the other side of the equation, in terms of the effect of prices on consumer demand, and in the sense that lentil and chickpea are consumed in popular routine dishes. A study was conducted in 1993 on the expenditure elasticity of demand for some food items in Jordan (Hamdan, 1993). This study revealed that the expenditure elasticity of demand was 0.90 and 0.38 for lentil and de-hulled lentil, respectively, while it was higher for 'Hummos chickpea' (exact figure not published). This means that the retail prices of lentil in local markets did not significantly affect consumer routine consumption of this protein crop. The consumer consumption of these crops in the diet is relatively stable. We can conclude that these crops are important in people's diets.

Publications:

Extension bulletins in Arabic detailing recommended practices have been produced for farmers and extension workers.

A 25-minute video in Arabic on mechanical lentil and chickpea production is available for use at workshops and in field days.

Implementation Status:

Concerning the previous Project that was concluded in 1992 (FLIMP), it had achieved several results. Those included the release of three lentil and three chickpea improved varieties and those concerned with the optimum cultural practices to be used in producing lentil and chickpea (land preparation, sowing date and rate, sowing method, sowing depth, fertilization, weed control, Brochus and Sitona control and harvest).

At the end of that project, socioeconomic studies were carried out to measure the extent to which farmers had adopted the recommended new technology inputs set by the project. The improvement in chickpea and lentil production methods fostered by this project led to increased yields of both legumes. Using improved cultivars, fertilizers, and other inputs contribute to improved yields. A number of socioeconomic studies have been carried out over the years revealing the following:

- A large number of farmers adopted either all or part of the project technology recommended (in the period of the concluded project (FLIMP).

- Many farmers began to include food legume crops in the crop rotation system instead of leaving fields fallow.

- There was an increase in total area planted with lentil and chickpea (in the period of the concluded project (FLIMP).

Success in developing this transferable technology, having it adopted by food legume farmers, and then realizing improved production and larger crops are factors contributing to the improved well-being of Jordanian farmers and their families.

The technology has been demonstrated as a full package to farmers who possess land holdings large enough to introduce mechanization (five hectares or more), and as a minimum input (improved varieties and fertilizers) to those with smaller, poorer farms. Seeds of improved varieties are propagated by the Ministry of Agriculture and JCO (now JACE) and distributed to participating farmers. Using the full scope of the recommended production method has doubled the yields of some farmers.

|

| Ascochyta blight on chickpea , Maru station, Northern Jordan |

The current FLIP at NCARTT at present has in pre-release multiplication promising lines of chickpea resistant to Ascochyta blight races and possessing relatively larger seed size, in addition, promising lines of lentil with larger seed size compared to the previously released varieties were developed.

Follow-up Strategy:

Lentil and chickpea research features to be considered:

- Identification of Aschochyta blight genotypes that affect chickpea crop in Jordan as a step toward a resistance variety (Technical capabilities for that are not available at the present time at NCARTT.

- More efficient control of Sitona weevil and Bruchus on lentil.

- Weed management in lentil and chickpea fields.

- Convenient means for harvesting lentil and chickpea.

- Improvement in lentil and chickpea seed quality specially seed size.

- Land tenure of farmers.

- Market competition.

Anticipated or Known Documentation Endeavors:

Extension leaflets, Annual Reports have been released. Scientific papers publications are expected in the near future.

Information Sources:

1. External Trade Statistics. 1986-1997. Department of Statistics. Amman, Jordan.

2. Food Legume Improvement and Mechanization Project (FLIMP). 1993. Annual report 1991/1992. Final report of phase III, 1988-1992. University of Jordan, Ministry of Agriculture/NCARTT in collaboration with International Development Research Center, Canada (IDRC). Amman, Jordan.

3. Food Legume Improvement Project Annual reports. 1993-1998. National Center for Agricultural Research and Technology Transfer (NCARTT). Baqa' Jordan.

4. General results for the agricultural Census. 1997. Department of Statistics. Amman, Jordan.

5. Hamdan, M.R.1993. Expenditure elasticity of demand and an estimate of the total demand for some food items in Jordan. In Arabic (English abstract). Dirasat. V.20b. No.4. p102.

6. Jordanian Agricultural Cooperative Establishment. Personal contact.

7. Nanish, N. 1996. Genetic Resources of Food Legumes In Jordan. In: Proceeding of National Seminar on Plant Genetic Resources of Jordan. 2-4 August 1994 Amman Jordan. pp. 75-87 Jaradat, A.A. (editor). IPGRI, Aleppo, Syria.

8. Snobar, B., Haddad N. 1993. Achievements of Food Legume Improvement Project (1980-1992): Project Activities and Achievements. University of Jordan Publications. 41 pp.

9. Statistical Yearbook. 1986-1997. Department of Statistics. Amman, Jordan.

Submitted by:

Nidal Nanish

Food Legume Improvement Project at

National Center for Agricultural Research and Technology Transfer (NCARTT),

Jordan

email: nidalnanish@yahoo.com

Additional Contact:

Abdel-Naby Fardous, Ph.D

Director General of NCARTT

Fax: 96264726099

Tel: 96264725411

P. O. Box 639

Baqa’ 19381

Jordan

http://www.ncartt.gov.jo/

National Center for Agricultural Research and Technology Transfer (NCARTT)

Information Date: 2000-03-10

Information Source: Nidal M.A.H. Nanish, Food Legume Improvement Project at National Center for Agricultural Research and Technology Transfer (NCARTT), Jordan.

Search

Latest articles

Agriculture

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Air Pollution

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Biodiversity

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Desertification

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- UN Food Systems Summit Receives Over 1,200 Ideas to Help Meet Sustainable Development Goals

Endangered Species

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

- Coral Research in Palau offers a “Glimmer of Hope”

Energy

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Wildlife Preservation in Southeast Nova Scotia

Exhibits

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Coral Reefs

Forests

- NASA Satellites Reveal Major Shifts in Global Freshwater Updated June 2020

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Global Climate Change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

Global Health

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- More than 400 schoolgirls, family and teachers rescued from Afghanistan by small coalition

Industry

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Natural Disaster Relief

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

News and Special Reports

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

Oceans, Coral Reefs

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Pollution

- Zakaria Ouedraogo of Burkina Faso Produces Film “Nzoue Fiyen: Water Not Drinkable”

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Population

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Public Health

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Rivers

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Toxic Chemicals

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Actions to Prevent Polluted Drinking Water in the United States

Transportation

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Urbanization Provides Opportunities for Transition to a Green Economy, Says New Report

Waste Management

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water and Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution