Navigation

George Schaller’s Wildlife Conservation Journeys in Tibet Wild

- Afghanistan

- China and Tajikistan

- chiru

- conservation

- disease

- Dr. Stephane Ostrowski

- game reserves

- George B. Schaller

- gorilla

- health

- lion

- Marco Polo sheep

- National Geographic

- Pakistan

- Pamir Mountains

- panda

- Peking University

- pika

- Rwanda

- Sanjiangyuan National Nature Reserve

- snow leopard

- Tarun Tejpal

- Tibet Wild

- tiger

- Virunga National Park

- Wildlife Conservation Society

- Biodiversity

- Endangered Species

- Forests

- Global Climate Change

George B. Schaller shares special moments throughout his book Tibet Wild: A Naturalist's Journeys on the Roof of the World, and tells of his connections with animals in ways that can benefit others in their pursuit of animal preservation. There are more than 20 game reserves around the world stemming from Schaller’s work.

500hr.jpg) George Schaller on the Tibetan Plateau.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

George Schaller on the Tibetan Plateau.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

“There are wonderful moments.

One day I was siting on a branch observing one of the groups of gorillas and a female gorilla came up on to the branch and sat next to me.

We sat there together.”

George B. Schaller shares special moments throughout his book Tibet Wild: A Naturalist's Journeys on the Roof of the World, and tells of his connections with animals in ways that can benefit others in their pursuit of animal preservation. There are more than 20 game reserves around the world stemming from Schaller’s work.

Schaller is pursuing his efforts to preserve tigers and other great cats as vice president of Panthera, an organization dedicated to “Ensuring the future of the great cats.”

Throughout this engaging book, George Schaller puts the animals he seeks to preserve in context describing their habitat, the cultures and traditions of the people whose lives and those of the wild animals are interdependent, and shares knowledge reaped from his half a century of dedication to their preservation.

George Schaller calls Tibet Wild, “a personal book of science, conservation, and exploration based on my observations, experiences, and feelings.” He has said he believes “Conservation is a moral issue coming from the heart.”

“I have always taken good opportunities when they are presented. In the 1950’s, I was asked ‘Would you want to go to study gorillas in Africa?’ Of course, you say yes,” Schaller said in a conversation with Tarun Tejpal at Tehelka's THiNK 2012. “ A lot of anthropologist said you cannot study gorillas in the wild they are too dangerous. Well, I know animals, if you are not armed, if you are gentle with them, they tolerate you. So, I moved up in the mountains.”

A scenic of the Virunga Volcanoes which straddle the Rwanda-Congo border and are the principal home of the mountain gorilla.: Photograph by and courtesy of George B. Schaller

A scenic of the Virunga Volcanoes which straddle the Rwanda-Congo border and are the principal home of the mountain gorilla.: Photograph by and courtesy of George B. Schaller

Schaller tells about his and his wife’s life with gorillas in Tibet Wild:

On February 1, 1959, Doc and I and our wives left for Africa to observe mountain gorillas, animals of such reputed belligerence that several scientists had warned that we had little hope of success. The New York Zoological Society sponsored our project, as it had the project in Alaska three years earlier. At first we visited all parts of the gorilla’s range in what is now Rwanda, Uganda, and the Congo (then the Belgian Congo) to obtain information on the distribution and ecology of this remarkable animal which ranged from the hot equatorial forest at about 1,500 feet above sea level up into cold mountains at 13,000 feet. The Emlens returned to Madison in July, but Kay and I stayed on to study mountain gorillas intensively. We had selected the Virunga Volcanoes in the Congo’s Albert National Park, now the Virunga National Park, as our base. Fifty-five porters carried a five-month supply of food and equipment into the saddle between two inactive volcanoes, Mount Mikeno and Mount Karisimbi. There at the edge of a small meadow surrounded by gorilla forest at 10,000 feet was a cabin of rough-hewn boards. It became our home for a year.

At first I tried to creep silently close enough to gorillas to observe them without the animals becoming aware of me. As described in The Year of the Gorilla (1964), I did obtain glimpses:

A subadult male, perhaps 7 years old, eating a stalk of wild celery.: Photograph by and courtesy of George B. Schaller

A subadult male, perhaps 7 years old, eating a stalk of wild celery.: Photograph by and courtesy of George B. Schaller

“A female gorilla emerged from the vegetation and slowly ascended a stump, a stalk of wild celery casually hanging from the corner of her mouth like a cigar. She sat down and holding the stem in both hands bit off the tough outer bark, leaving only the juicy center which she ate....”

Even observations as mundane as this were new and exciting, recording peaceful activities as no one had done before. But I wanted more intimate contact—I wanted rapport. Instead of hiding, I decided to settle myself in full view of the gorillas on a low branch of a tree. The gorillas were more curious than afraid: “They congregated behind some bushes, and three females carrying infants and two juveniles ascended a tree and tried to obtain a better view of me. . . . Junior, the only black-backed male in the group, stepped out from behind the shrubbery and advanced to within ten feet of the base of my tree.”

I identified ten gorilla groups around our cabin, ranging in size from eight to twenty-seven members and totaling 169 animals. Each group was led by an adult or “silverback” male. The faces of gorillas are so distinctive that I recognized them all and knew them by name. The gorillas now were our neighbors, our kin, beautiful in their shiny blue-black pelage and kindly, brown eyes. Kay and I gossiped about them: “Mrs. Patch had a quarrel with Mrs. Blacktop; Calamity Jane let her baby ride on her back for the first time; the injured eye of Mrs. Bad-eye looks worse.”

After many days in close contact, so tolerant were some groups that I could spend day and night with them. One night, I decided to sleep near Big Daddy and his family. Toward dusk, I settled myself quietly near Big Daddy and watched as he reached out to bend the branch of a shrub and push it under a foot. He pulled in all other branches within reach, rotating slowly, until he had constructed a crude nest around his body. After that he reclined, legs and arms tucked under, his silver back toward the sky. At half past five, Big Daddy slept and so did all twenty-three other members of his group. Quietly I placed a tarp on the ground and unrolled my sleeping bag on it. I could hear the rumble of gorilla stomachs as I fell asleep, not the least concerned about being so close to these apes. I had spent nights with gorillas before, and had always been treated as an innocuous creature at the periphery of the group. Not until seven o’clock, after the morning sun had climbed over the distant ridge, did two females rise and wander slowly around, but Big Daddy rested awhile longer.

No one had ever before delved into the private life of gorillas, one of our closest relatives, as I was doing now. I was interested in everything about their daily routine, their food habits, their social interactions within and between groups, the extent of their travels—all basic aspects of their existence in these cloud-shrouded mountain forests. Naturally, I was also intrigued by how their society compared with that of humans. But beyond that, I knew that information about the needs of this rare and beautiful ape was essential for protecting it and its habitat. Our months with the gorillas were idyllic, as well as contributing something new to science and conservation.

A female relaxing in the lush mountain vegetation.: Photograph by and courtesy of George B. Schaller

A female relaxing in the lush mountain vegetation.: Photograph by and courtesy of George B. Schaller

"No one who looks into a gorilla's eyes – intelligent, gentle, vulnerable – can remain unchanged, for the gap between ape and human vanishes; we know that the gorilla still lives within us,” Schaller wrote in his book, Gentle Gorillas, Turbulent Times. “Do gorillas also recognize this ancient connection?"

Prophet Earth - George Schaller at THiNK 2012

George Schaller in conversation with Tarun Tejpal at Tehelka's THiNK 2012 session on "The Saint of Lesser Beings: How One Man Protects a Planet" Published on Nov 19, 2012

In Schaller’s conversation with Tejpal, Schaller says “There is not much separating us. Gorillas are our close kin. You see a big beautiful gorilla you want to put your arm around it.”

“If you do that, you live to tell the tale?” asks Tejpal.

“No. I don’t do think it is a good idea to touch them because humans have a lot of diseases which you can transmit.”

Tajpal asks, “At what point did you exit the gorilla …what was the process by which the preservation of gorillas became a success?”

“Other people have taken it over and continued and continued. I go back occasionally to say hello to the gorillas.”

George Schaller's message to the Year of the Gorilla

World renown conservationist George Schaller, one of the first to look at gorillas from a modern, scientific perspective, gives a recount of his experiences and an outlook on the future and obstacles of gorilla conservation. Uploaded on Jun 25, 2009

Schaller’s seminal work with gorillas led to the lifelong work of Dian Fossey, whose 18 years of living with Mountain Gorillas was depicted in the Academy Award-wining film Gorillas in the Mist.

.jpg) The kiang, a species of wild ass unique to the Tibetan Plateau, has increased in number with better protection in recent years.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

The kiang, a species of wild ass unique to the Tibetan Plateau, has increased in number with better protection in recent years.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

As National Geographic writer Scott Wallace wrote in “Lifetime Achievement: Biologist George Schaller,” in 2007, “By focusing on large, captivating animals, Schaller has had remarkable success inspiring people to protect entire ecosystems.

to 240 search.jpg) Our guide in Tajikistan scans the terrain for Marco Polo sheep. The Mustagh Ata massif across the border in China is in the: background. Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.After 50 years of fighting to save the world's endangered creatures, George Schaller has got it down to a science. But in Afghanistan—home to the Marco Polo sheep—the biologist must contend with murky tribal politics and rogue opium dealers…Schaller had come to this remote corner of the western Himalaya in pursuit of perhaps the most ambitious project of his 50-year career: the creation of an international peace park in a vortex of strife that stretches across parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan, China, and Tajikistan.

Our guide in Tajikistan scans the terrain for Marco Polo sheep. The Mustagh Ata massif across the border in China is in the: background. Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.After 50 years of fighting to save the world's endangered creatures, George Schaller has got it down to a science. But in Afghanistan—home to the Marco Polo sheep—the biologist must contend with murky tribal politics and rogue opium dealers…Schaller had come to this remote corner of the western Himalaya in pursuit of perhaps the most ambitious project of his 50-year career: the creation of an international peace park in a vortex of strife that stretches across parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan, China, and Tajikistan.

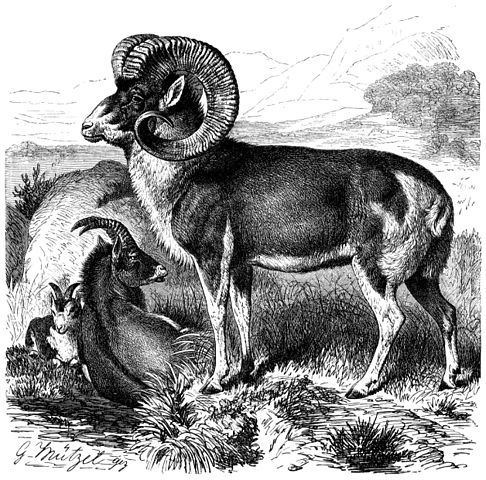

Marco Polo sheep rams.: Engraved by Gustave Mützel Published 1883 at the latest- this version of the book published then, may have appeared in earlier books. Courtesy of ZWikipedia from Brehm, Alfred/Brehms Thierleben/Säugethiere/Vierte Reihe: Hufthiere/Elfte Ordnung: Wiederkäuer (Ruminantia)/Sechste Familie: Hornthiere (Cavicornia)/23. Sippe: Schafe (Ovis)/Katschkar (Ovis Polii) Katschkar (Ovis Polii).1/17 natürl. Größe.

Marco Polo sheep rams.: Engraved by Gustave Mützel Published 1883 at the latest- this version of the book published then, may have appeared in earlier books. Courtesy of ZWikipedia from Brehm, Alfred/Brehms Thierleben/Säugethiere/Vierte Reihe: Hufthiere/Elfte Ordnung: Wiederkäuer (Ruminantia)/Sechste Familie: Hornthiere (Cavicornia)/23. Sippe: Schafe (Ovis)/Katschkar (Ovis Polii) Katschkar (Ovis Polii).1/17 natürl. Größe.

The proposed park's most celebrated inhabitants are dwindling herds of Marco Polo sheep—the world's largest and most magnificent wild sheep, which share the labyrinthine, windswept valleys of the Wakhan corridor with nomadic communities of Wakhi and Kyrgyz herders.”

"So you're fighting not just for the sheep but for the whole environment, all the plants and animals in this area," Scott related.

"My focus is on the sheep, because it's the most conspicuous animal here," said Schaller.

“It's a strategy that Schaller, the vice president of science and exploration at the Wildlife Conservation Society [WCS], has employed again and again to become perhaps the greatest force for conservation in more than a century,” wrote Scott.

“This magnificent animal, the grandest of all wild sheep, roams across several international borders,” writes Schaller in Tibet Wild in which he portrays the collaborative efforts to create the peace park in the context of saving the Marco Polo sheep.

“To protect and manage it requires cooperation between Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and China, something best achieved by the creation of a four-country International Peace Park or Trans-Frontier Conservation Area. 340 wed to.jpg) Kirghiz women in the Afghan Pamirs wear their finery, including necklaces of silver coins, at a wedding.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.My efforts to promote this goal after working in each of the four countries, some of them politically volatile, provide me still with some useful lessons, about patience and persistence above all.”

Kirghiz women in the Afghan Pamirs wear their finery, including necklaces of silver coins, at a wedding.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.My efforts to promote this goal after working in each of the four countries, some of them politically volatile, provide me still with some useful lessons, about patience and persistence above all.”

The borders of these four countries in the Pamir Mountains of Central Asia “meet at this confluence of stunning mountain peaks and deep valleys,” The Wildlife Conservation Society explains. “There is a critical need for coordinated conservation and development efforts among the four countries. This would ensure that the native wildlife continues to thrive and that the communities of these mountains enjoy improved livelihoods through better management of their resources.”

“In Tajikistan, WCS met repeatedly with the central government authorities to encourage their participation in a transboundary initiative. We have also surveyed wildlife and studied disease interactions between livestock and Marco Polo sheep in the Pamir region.”

“Preserved in formalin, one tube for each animal, the droppings will later be analyzed by veterinarian Stephane Ostrowski of the Wildlife Conservation Society and his Chinese coworkers to see if they contain parasites such as the eggs of roundworm and tape worm, or any of various protozoans,” Schaller writes. “This will determine which parasites are shared between wild and domestic animals and might affect health.”

Ostrowski wrote in response to my request for his account for this article: “Health is of major concern in Tibet,” “The combination of elevation, isolation, and intense poverty makes any solutions or improvements difficult, and a fundamentally new approach is needed to address health threats at an appropriate scale. The extreme inter-dependencies among animal, human and ecosystem in Tibet call for health responses that are equally interdependent and multidisciplinary. By using the samples forwarded to us by George we were interested to know which type of parasites occurred in wild ungulates, whether they had the potential to be shared with livestock and even be of concern to people. Although collecting feces of wildlife in the remotest areas of continental Asia may appear strange or even futile for the man in the street, George understood that it could help researches that will protect wildlife from dangerous diseases they may encounter when in contact with livestock, and at the same time bring significant health improvement to the poorest.”

to 500.jpg) Our night camp in the spacious northern Chang Tang. In our west to east traverse, we did not encounter any people in 1000 miles: of cross-country driving. Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

Our night camp in the spacious northern Chang Tang. In our west to east traverse, we did not encounter any people in 1000 miles: of cross-country driving. Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

Pursuing protection of our world’s magnificent animals while assisting communities takes Schaller to the far corners of the world. The Chang Tang Nature Reserve, established in 1993 by the Tibet Autonomous Region, in part due to Schaller’s work, was made a national reserve. It covers, according to Tibet Wild, about 115,000 square miles. Chang Tang Nature Reserve was called "One of the most ambitious attempts to arrest the shrinkage of natural ecosystems," by The New York Times. Schaller recalls that it was necessary to unravel the problem of how to keep the chiru population safe in this vast area which was also home to 4,000 families at the time. “The region was so vast that there were not enough vehicles, personnel and funds to sustain antipoaching efforts, especially not in uninhabited terrain.”

to 500.jpg) Two male chiru in striking nuptial pelage pose during the December mating season.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

Two male chiru in striking nuptial pelage pose during the December mating season.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

to 240.jpg) A chiru female with a month-old calf is migrating south from the calving ground to better pastures.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

A chiru female with a month-old calf is migrating south from the calving ground to better pastures.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

Throughout much of Tibet Wild, Schaller writes about the chiru: “It affords me great pleasure to observe the rich and complex life of another species and to write its biography. After all, the mountain gorilla, tiger, giant panda, and chiru are among the most beautiful expressions of life on Earth.”

He realized that “To be saved, the migratory chiru populations must be protected on their winter range, along their migratory routes, and, importantly, on the calving ground where they are concentrated and most vulnerable.”

Of an expedition into Nepal’s mountains, in Tibet Wild he writes:

In central Nepal, we follow a dozen porters carrying enough food and equipment for a month up a gorge in the shadow of 26,800-foot Mount Dhaulagiri. Huge cliffs flank us on one side and a torrent on the other. Here and there on more gentle terrain are huts and fields and, high above, stands of forest. It is March, not yet spring. The air is hazy from fires that consume tussock grass, and fanned by wind, roar through conifer forests; the casual vandalism by these Tibetan villagers is destroying the last forests upon which they depend for timber and fuel. When Hamid, who speaks Tibetan, asks a man why they set fires, he replies with the desolate words, “We have always burned.” We raise the same issue with a Hindu official from the lowlands who is posted here against his will. He responds, “What to do?” as he waggles his hands.

to 500.jpg) Porters climb toward a pass, the Doxiong La, across which lies the ‘hidden land’ of Pemako in southeastern: Tibet. Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

Porters climb toward a pass, the Doxiong La, across which lies the ‘hidden land’ of Pemako in southeastern: Tibet. Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

When he encountered conflicts with the teachings of a lama, Schaller handled the situation delicately:

When we meet the lama, a lithe, intense man perhaps in his late forties, we ask him about all the discordant development. He explains that foreign donors make the construction possible. His goal is to expand the dharma, the ideal truth leading to salvation, by training many monks and nuns and educating many children. His vision is growth. We point out that the dharma is threatened if the land is degraded, that Sertang is too small for such a large community. Many hemlock and fir, two hundred years old, have already been felled, with most of the wood left to rot after only a little of it has been used for roof shingles. Why are the tahr protected but not ancient trees? The lama replies, “Trees don’t meditate.” They have no nervous system like animals and because of that are not sentient beings. I explain that research has shown that plants can communicate with each other. Does that not make them sentient? I have noted in both monks and laymen that religious conviction about living beings, about nature, seldom includes ecological awareness and understanding. Sertang, we realize, represents in a microcosm the worldwide conflict between development and the moral values of conservation.

500hr.jpg) Near the village of Zhachu in southeastern Tibet, the Yarlung Tsangpo roars through the deepest gorge in the world: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

Near the village of Zhachu in southeastern Tibet, the Yarlung Tsangpo roars through the deepest gorge in the world: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

In the regions between China and India, Schaller takes readers to a fascinating region with vivid description of its early explorers’ findings:

The Yarlung Tsango roars down a canyon between the two peaks that I had seen from the air, 25,446-foot Namche Barwa and 23,461-foot Gyali Peri (Gyala Balei), only thirteen miles apart. To the east of Namche Barwa are forested hills which in the north are guarded by the high Kangrigarbo Range and in the south by a disputed, closed border, the Line of Control separating China and India. Here, subtropical rain forest at 3,000 feet and perpetual snow and ice at 14,000 feet are only a few miles apart.

One of the fascinating chapters of Asian history is the exploration of this region, mainly by the British during the first half of the twentieth century. It was known in the early 1900s that the Yarlung Tsangpo flowed some 700 miles from west to east in Tibet. But then where did it go?

pika to 340.jpg) The plateau pika is a key species in maintaining biological diversity in the Chang Tang yet is considered: a pest and poisoned. Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.Among the many concerns about harm to the animals, Schaller addresses the poisoning of the pikas, small animals with rounded ears and now external tail that inhabit rocky mountainsides in cold climates of North America and Eastern Europe in addition to Asia, their main habitat. “Pikas, people, livestock, and rangelands have existed together for several thousand years, their lives connected without acrimony,” Schaller writes, “Almost everyone from government official to herdsman now recognizes that vast tracts of rangelands have been degraded by too much livestock. Yet the pika is still being made a scapegoat.”

The plateau pika is a key species in maintaining biological diversity in the Chang Tang yet is considered: a pest and poisoned. Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.Among the many concerns about harm to the animals, Schaller addresses the poisoning of the pikas, small animals with rounded ears and now external tail that inhabit rocky mountainsides in cold climates of North America and Eastern Europe in addition to Asia, their main habitat. “Pikas, people, livestock, and rangelands have existed together for several thousand years, their lives connected without acrimony,” Schaller writes, “Almost everyone from government official to herdsman now recognizes that vast tracts of rangelands have been degraded by too much livestock. Yet the pika is still being made a scapegoat.”

Tibet Wild tells many stories about other animals Schaller has worked to preserve from the tigers of India to the snow leopard.

Schaller philosophizes in Tibet Wild: “But what has been has been, and I have had my hour,” wrote the seventeenth-century poet John Dryden. Indeed I have. But I hate to acknowledge this. I cannot resist returning to the solitude of these vast uplands. With each expedition, I slough off my past like a snake skin and live in a new moment. Marooned in mind and spirit, I have no idea when my work there will end; I continue to plan new projects. But like all good ventures it will end someday without heroics.

kay 500.jpg) My wife Kay clips vegetation on a plot to determine biomass, species composition, and diversity.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

My wife Kay clips vegetation on a plot to determine biomass, species composition, and diversity.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

Tibet Wild: A book dedicated to “my companions on these many journeys into the wild.” For most of his years of exploration, Schaller’s lifelong companion, his wife Kay, was with him, a helping in many ways. While she was not able to be with him for the recent journeys he writes about in this book, Kay edited this manuscript.

On the day after his return from his latest trip to China, George Schaller graciously took time for me to interview him for this article. By Janine Selendy, Chairman, President and Publisher of Horizon International

Q: You write in your introduction to Tibet Wild:

“ I hoped to collect enough scattered facts to discover from them certain patterns and principles which underlie the Chang Tang ecosystem. But nothing remains static, neither a wildlife population nor a culture, and I knew my efforts would represent just a moment in time, a record of something that no one has seen before and never would again. My information offers the landscape an historical baseline, drawn over a three-decade period from which others working in the future can reclaim the past and compare it to their present. Because the Tibetan Plateau is being rapidly affected by climate change, the accumulation of such basic knowledge has now become especially timely and urgent.”

What were your objectives for this trip, where did you go, and how much time did you have? Did you go to areas discussed in Tibet Wild?

A. No, I was mainly in meetings on this trip. I am working with Peking University on a huge conservation project.

There is now one-third of Tibet preserved as nature reserves. There is a need to protect the headwaters of the main rivers of China, to protect the environment in order to establish an ecological civilization that includes wildlife rangeland, and everything else.

One has to go slowly and work with thousands of communities in order to succeed with preservation efforts.

Herdsmen need training to protect the environment. They need to realize that they cannot have too much livestock. This is a hard lesson. Many herdsmen are becoming sedentary instead of nomadic. They build fences for their animals and, encouraged by the immediate economic rewards, they are encouraged to keep enlarging their herds without realizing the limitations of grazing land.

One needs to manage landscape and people imaginative ways with a bottom up approach with each community.

It is necessary to monitor wildlife and rangelands and to train trainers. Governments, communities, and NGOs all need to cooperateIn order to be successful.

“As I write this, I feel like a lawyer making a case in defense of an innocent victim. However, not until 2006 was I actually witness to the crime being committed. Up to that time the pika’s travails were of concern, but my emotions were not deeply involved. That changed when we came into contact with a mass-poisoning campaign in the winter of 2006 after we had crossed the Chang Tang in a traverse west to east.”

“That the poison pogrom occurs in the Sanjiangyuan National Nature Reserve, [150,000 sq km reserve] is particularly distressing. This huge reserve, established with a national mandate in 2003, has as its explicit purpose the preservation of the full ecosystem with all its plants and animals in order to help maintain the livelihood of Tibetan communities. With the reserve including the headwaters of three great rivers, the Yellow, Yangtze, and Mekong, habitat preservation is essential if the millions of people living in the lowlands downstream are to be assured an adequate water supply. Yet the poisoning mindlessly degrades rangelands and reduces biological diversity.”

Q: What advice would you give to individuals and organizations -- local, national and international—seeking to help with preservation efforts today, ones that might endure?

Giant Panda.: Photograph by J. Patrick Fischer, taken in Ocean Park, Hongkong Courtesy of WikipediaA: My advice is for you to pick the places that you think is beautifully, get emotionally involved with animals like the lion, gorilla, panda, and so forth, and fight on its behalf. You need to work with local people and be prepared to spend years. You can never turn your back. You will you need to train people to take over for when you can no longer be there.For example, Pan Wenshi, panda biologist, started his own initiative and trained students who are now professors. Pan Wenshi was one of Schaller's co-workers in Wolong along with Hu Jinchu who was the leader of the project. Schaller, Pan Wenshi, Hu Jinchu and Zhu Jing co-authored the book The Giant Pandas of Wulong.

Giant Panda.: Photograph by J. Patrick Fischer, taken in Ocean Park, Hongkong Courtesy of WikipediaA: My advice is for you to pick the places that you think is beautifully, get emotionally involved with animals like the lion, gorilla, panda, and so forth, and fight on its behalf. You need to work with local people and be prepared to spend years. You can never turn your back. You will you need to train people to take over for when you can no longer be there.For example, Pan Wenshi, panda biologist, started his own initiative and trained students who are now professors. Pan Wenshi was one of Schaller's co-workers in Wolong along with Hu Jinchu who was the leader of the project. Schaller, Pan Wenshi, Hu Jinchu and Zhu Jing co-authored the book The Giant Pandas of Wulong.

Q. What is the status of the Mountain Gorilla in Rwanda today:

A. Rwanda has done a fantastic job. They have names for all of the gorillas, nearly 200 of them. So, if one is missing, they know and try to find out what happened.

Rwanda has one of most dedicated guard forces I have ever seen. Guards get killed protecting gorillas. Once a year there is a huge naming ceremony [called Kwita Izina] held in the Virunga mountains in Northern Rwanda. [This year in June, Rwandans celebrated the birth of 12 baby gorillas at an event attended by thousands of residents of the Musanze District and international visitors.] The guards know the names of the gorillas, named in recognition of those who care for them including the communities, guards and veterinarians.

Tourism is very strict. For an hour with the gorillas, tourists pay $ 500, a large portion of which goes to the communities so they will protect the gorillas.

Q: This is a great example. According to the government of Rwanda, these naming ceremonies, now the 9th, have been a major factor in the conservation efforts and have helped lead to a 26.3% increase in the local population of gorillas since 2003.

A. “That is something that can be emulated in India and in other countries.”

Q: What is the status of your effort to “establish a reserve shared by Afghanistan, Pakistan, China and Tajikistan"?

A. In 2006, the four countries met about the peace park in China and agreed to it. Naturally there are then problems, given the various governments…Tajikistan is the major hold-out about doing anything, foreign hunting outfits like Safari Club International lobbying against things because they are afraid that killing Marco Polo sheep will be prohibited from hunting [the Marco Polo sheep] which is not true. Anyway, these things take time.”

A phantom of the peaks, the snow leopard is difficult to spot even when in full view.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

A phantom of the peaks, the snow leopard is difficult to spot even when in full view.: Photograph from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press.

In response to my questions to Schaller regarding the status of the transboundary conservation in the Pamirs, Dr. Ostrowski and Peter Zahler, Deputy Director, Asia Program, WCS provided this update on the 1st of December 2013:

Dr. Ostrowski wrote from Afghanistan, that “in Pamir, my duty is to second Peter Zahler in raising awareness and, ultimately, funding to develop a landscape-scale conservation project that will overlap range states sharing the Pamirs. At the moment we … developing a cooperative rapprochement between range states through focal meetings and small scale transboundary science.”

Zahler added: Dr. Ostrowski and I have been working these last few years with George to help bring George’s goal of transboundary conservation in the Pamirs into reality (an idea first suggested by a Russian almost a hundred years ago now, but which lay fallow until George began talking and writing and working toward it in the 1970s). Our recent efforts started with a four-country transboundary conservation meeting in Urumqi in 2006, with high-level delegates from China, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan, where a suite of recommendations were approved and an agreed-upon draft map was created for a possible transboundary protected area. We then shifted gears to actually implementing the recommendations from Urumqi. Since 2006 we have helped build natural resource governance structures in 55 communities covering all of the Afghan Pamirs (Wakhan) and 65 communities in Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan Province, with roughly 200 community rangers now patrolling the region and monitoring wildlife. We have also been performing research and focused conservation initiatives on some of the iconic wildlife of this region, such as collaring and tracking snow leopards and studying Marco Polo sheep. We also held a meeting on transboundary conservation in Dushanbe in 2011 and Stephane ran a three-country transboundary health project in 2011-2012 (looking at livestock disease issues in each country and bringing together health experts in the three countries to discuss methods, results, and next steps); and next spring we hope to hold a three-country (Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan) transboundary meeting on climate change in the Pamirs.

Q. How do you involve young people with your work?

A. I take graduate students from Peking University to study nature and the local societies. We collect information needed about species and about the ecosystem and local cultures.

Q. In Tibet Wild, you wrote, “It is a lesson that nothing is safe, that if a country treasures something it must monitor and guard it continually.”

A. “As long as there keep being enthusiastic young people who carry on the work, who will then train others and continue on and on…will a species existence be secure.

Q. “Do you feel optimistic about the future of the animals and places you studied?

A: Definitely. Governments are much more aware now about the need for conservation. For example, oil companies have so far been kept out of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge; mountain gorillas are slowly increasing in Rwanda and have now reached a level at which they were in 1960; India is making a much greater effort to protect its tigers, establishing two new tiger reserves this year alone; the great herds and the lions in the Serengeti continue to thrive and threats, such as a major highway and railroad across the park are on hold because of an international outcry when these plans were announced; giant pandas are increasing in number and reserves, of which there were 11 in 1980, now total over 60; on the Tibetan Plateau, the Tibetan antelope are bouncing back after large-scale poaching has been reduced and the Chinese government has seriously focused on protecting the ecosystems, such as establishing a series of contiguous reserves in the northern part over 200,000 square miles in size, similar to that of California or Germany.

Text and images, as noted, from Tibet Wild by George B. Schaller. Copyright A 2012 George B. Schaller. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington" D.C.

Tibet Wild: A Naturalist’s Journeys on the Roof of the World By George B. Schaller © Island Press (October 2012) www.islandpress.org/tibetwild, http://islandpress.orglip/books/book/islandpress/T/bo8454583.html

A video about George Schaller, Ph.D., by the

George Schaller, Ph.D., the world's preeminent field biologist, is with the Wildlife Conservation Society and has traveled across the globe to work with a variety of species, including two rediscovered species once thought extinct. Schaller began studying mountain gorillas near Rwanda more than 40 years ago, well before Dian Fossey earned recognition for her work through the film "Gorillas in the Mist". He was the first to show how gorillas are really gentle and intelligent, with a highly developed social and family structure, rather than the savage monsters that had been previously depicted. Uploaded on Nov 12, 2008

George Schaller's is Vice President of Panthera, an organization whose “rangewide initiatives and projects span over 50 countries and are carried out on behalf of the world's 37 species of wild cats. Panthera's core focus is on the largest, most imperiled cats - tigers, lions, jaguars and snow leopards.”

This article was published on the Horizon International Solutions Site on 1 December 2013.

Search

Latest articles

Agriculture

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Air Pollution

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Biodiversity

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Desertification

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- UN Food Systems Summit Receives Over 1,200 Ideas to Help Meet Sustainable Development Goals

Endangered Species

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

- Coral Research in Palau offers a “Glimmer of Hope”

Energy

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Wildlife Preservation in Southeast Nova Scotia

Exhibits

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Coral Reefs

Forests

- NASA Satellites Reveal Major Shifts in Global Freshwater Updated June 2020

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Global Climate Change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

Global Health

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- More than 400 schoolgirls, family and teachers rescued from Afghanistan by small coalition

Industry

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Natural Disaster Relief

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

News and Special Reports

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

Oceans, Coral Reefs

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Pollution

- Zakaria Ouedraogo of Burkina Faso Produces Film “Nzoue Fiyen: Water Not Drinkable”

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Population

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Public Health

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Rivers

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Toxic Chemicals

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Actions to Prevent Polluted Drinking Water in the United States

Transportation

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Urbanization Provides Opportunities for Transition to a Green Economy, Says New Report

Waste Management

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water and Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution