Navigation

Developing Urban Health Systems in Bangladesh

Since 1998, a promising partnership for health has been forming in Saidpur and Parbatipur municipalities in Northern Bangladesh. Under a Child Survival Programme (CSP), a tripartite partnership has developed between Concern, two municipal authorities, and 24 ward health committees (WHC).

Introduction

Since 1998, a promising partnership for health has been forming in Saidpur and Parbatipur municipalities in Northern Bangladesh. Under a Child Survival Programme (CSP), a tripartite partnership has developed between Concern, two municipal authorities, and 24 ward health committees (WHC). The CSP’s goal is to reduce maternal and child mortality and morbidity, and increase child survival by developing a sustainable municipal health service.

The programme aims to strengthen municipalities’ capacity to deliver quality maternal and child health interventions, which can be sustained using the existing resources of the municipality. These health interventions include providing immunisation, vitamin A supplements, maternal and newborn care, the integrated management of childhood illnesses, and promoting community health. Both the municipality and local community were involved in developing the service, which now reaches over 200,000 residents with improved health practices and services. Local stakeholders retained control of priorities, strategies and plans, which enabled high levels of their participation.

|

| Claudia Liebler and Scott Fisher facilitate an A1 training session Photo by: Dipankar Ditta |

Programme partners

The municipal authority

The municipal authority’s health department is the key programme actor. The municipal authority is composed of the cabinet, which consists of elected public representatives, and a secretary employed by the Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (MOLGRD). An elected chairman heads the cabinet.

The health department is supposed to be headed by a medical officer teamed with a supervisor and health workers. In reality, this head position is usually vacant because of the difficulty in attracting medical doctors due to limited career advancement. In the absence of a medical officer, the secretary is in charge. The CSP programme targets the supervisor and health workers as they are directly involved with the day-to-day maternal and child-related health services.

|

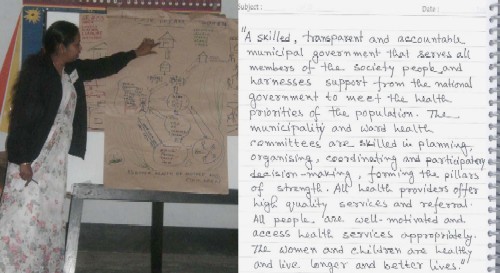

| A1 dream phase and dream statement for a sustainable municipal health system Photo by: Leo Ryan |

Ward health committees

The ward is the smallest represented unit of the municipality population. Each municipality is required by law to have a ward health committee (WHC), according to a government circular dated 28 November 1995, although such committees are almost non-existent in practice. The WHC should include the ward commissioner, ward secretary, a community health volunteer, representatives from NGOs, representatives from private service providers (e.g., rural medical practitioners, traditional birth attendants), ward municipality health staff, sub district-level health staff working in the ward, and key community workers and leaders, e.g. religious leaders, teachers, social workers, and leaders of community-based organisations. The WHCs are mandated to coordinate health and family planning activities for their residents; to ensure health education sessions in schools and satellite clinics; and to take necessary steps for treatment or hospital referral by collecting funds locally.

Mobilising the partners

Concern launched the programme in Mymensingh and Saidpur municipalities, where it had been providing primary healthcare services in slum clinics since 1972. It was hoped that Concern’s good reputation would help to build relationships with the municipalities and in turn facilitate a shift to system building and coordination.

The broken partnership

The CSP partnership with Mymensingh municipality started in August 1998. But following elections in February 1999, the Mymensingh municipality cabinet changed. The new cabinet argued that the proposed CSP programme strategy could not benefit the municipality unless some logistical support was provided, which included seven ambulances, salaries for municipal health staff and 21 health centres. Providing this logistical support was out of CSP’s scope. The partnership was broken and Concern had to withdraw the CSP from Mymensingh.

Learning from failure

After this Concern went through a self-assessment process. The analysis revealed that Concern was accustomed to negotiating with powerful donors, or weak counterparts. Concern did not have the skills to negotiate with powerful partners who saw things very differently to them. In addition, the CSP staff members were unclear about the capacity-building approach. So Concern undertook an intensive orientation with staff at programme and country office level on every detail of the CSP mission. This was followed by intensive staff training to build facilitation skills.

|

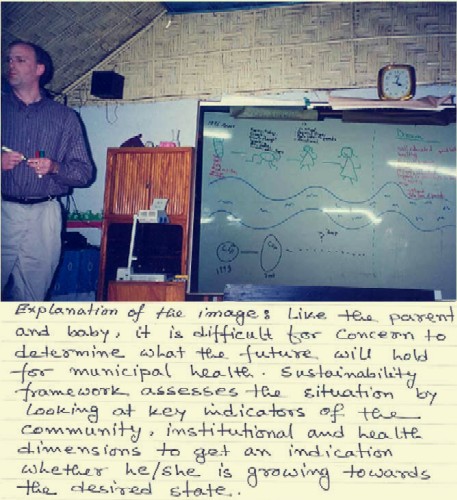

| Leo Ryan facilitates a session to orient Concern staff about sustainability Photo by: Michelle Kouletio |

|

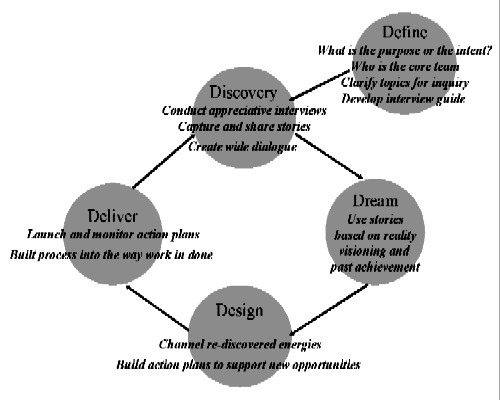

| 4D cycles of A1 |

Partnership building

Starting dialogue with the Saidpur municipality was also very challenging. Health had never been one of their main priorities. Public representatives preferred to gain votes by working on more tangible issues. As a result, the benefits of an intangible programme like the CSP were difficult for them to grasp. Nevertheless, Concern staff managed to overcome these constraints by:

- gradually building a good rapport with cabinet members and health staff;

- clarifying the municipality’s role according to national policy;

- clarifying the CSP strategies and approach, and fostering acceptance and recognition;

- organising workshops where cabinet members, ministry resources staff and other institutions could discuss the role of the municipality as a primary healthcare service provider; and,

- conducting a number of participatory baseline health assessments involving municipal health staff, sub district level health staff, community health volunteers and CSP staff.

This was very effective in making the municipal staff aware of their roles and responsibilities in terms of health service delivery and CSP goal and strategy.

This process of partner orientation and mobilisation was time-consuming. But it was invaluable for developing mutual understanding, trust and clarity on mutual roles and responsibilities for implementing the CSP. This encouraged commissioners to form a Ward Health Committee (WHC) in their respective wards.

Ensuring the effective participation of socially excluded groups in WHCs was always a key challenge for CSP and for Concern. However, because of the membership criteria set by the government, Concern found that socially excluded people could only participate in WHCs as leaders of community organisations. So the CSP conducted a number of focus group discussions with the community and local NGOs to identify which community organisations represented socially excluded people in Saidpur and Parbatipur. They identified three main groups: sweepers (untouchable class), non-Bengalis (politically marginalised), and extremely poor Bengali families (socio-economically marginalised). CSP staff also identified a few community-based groups organised by NGOs, which had representatives from extremely poor families, mainly vulnerable women. Based on this information, CSP wanted to try and ensure the participation of the leaders of these groups in the new WHCs.

Each ward held a public meeting in an open field. Both the CSP staff and ward commissioners jointly facilitated the meetings. Ward commissioners invited key community workers and leaders (already members of the WHC) and leaders of socially excluded groups. However, these leaders did not have a strong voice in the meeting at that time. For many it was the first public meeting they had ever attended. So Concern helped to ensure that the ward commissioners discussed the importance of representing these groups in the WHCs. This motivated the community to also select representatives from them. The total membership of the WHC ranges from 19-25 people.

This participatory process attracted the attention of the neighbouring Parbatipur municipality. Cabinet members there expressed their interest in working in partnership with the CSP. In contrast to Saidpur, they started negotiations with Concern to launch their own CSP. Following a series of discussions, Concern shifted the programme from Mymensingh to Parbatipur.

Capacity assessment of partners

After developing the partnership it was necessary to conduct a Health Institution Capacity Assessment (HICAP) to understand the strengths and weaknesses of both municipalities and to develop a capacity-building plan. The issue was very sensitive. We considered a number of factors when choosing the right technique.

- The assessment process should in itself be empowering for the municipalities.

- The process should include a wide range of stakeholders, including municipality cabinet members and health staff. Community members were not directly involved in the organisational capacity assessment, as usually only members of the organisation participate.

- The process should be sensitive to the culture of local government organisations, such as showing respect for leaders, working within a bureaucracy, etc. Most capacity assessment tools often analyse organisational weaknesses and then suggest ways to strengthen the organisation. Usually, these processes highlight bureaucracy, corruption, accountability, etc. as the key weaknesses. To keep a positive focus, we decided to conduct the capacity assessment based on organisational strengths.

- The process should suit municipality cabinet members’ level of awareness about capacity-building. Their activities are usually centred on gaining votes. Capacity assessments and capacity-building approaches have no direct visible outcomes. We wanted to introduce a process that first examined organisational strengths for which cabinet members could feel proud, and then focus the process on how capacity-building could make the organisation more effective.

We chose a process called Appreciative Inquiry (AI) (Cooperrider and Whitney, 1999). We organised two separate capacity assessment workshops with two municipalities, attended by municipality cabinet members and health staff.

|

| The community assesses the impact of the programme” Photo by: Dipankar Datta |

Using Appreciative Inquiry (AI)

AI is an approach that selectively seeks to locate, highlight and illuminate the dynamic forces within an organisation. We used an AI change process called the 4D Model: Discovery, Dream, Design, and Deliver.

- The discovery phase identified what gave the organisation life. We conducted appreciative interviews with municipality cabinet members and health staff, emphasising positive experiences and stories of excellence. For many, it was the first time they had been invited to think like this.

- The dream phase encouraged participants to visualise what a positive future might look like. Small groups formed to pull the elements of their visions together into a picture. The dream phase was both practical (grounded in the municipality’s history) and generative (as it sought to expand the organisational potential).

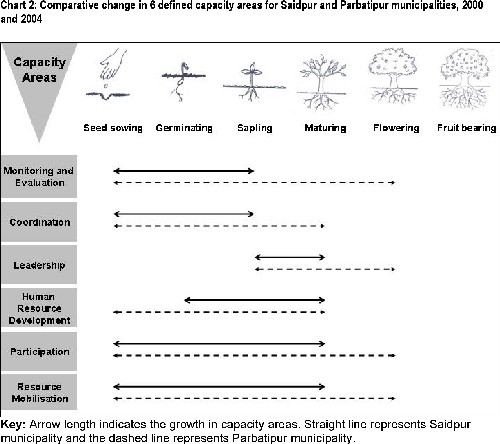

- The design phase looked into designing a process by determining specific short- and long-term targets towards achieving the dream. Here we identified capacity areas, and analysed the existing capacity by using a visual scale (see Chart 2) and developed a capacity-building action plan to achieve the targets.

- The delivery phase covered the launching and monitoring of capacity-building action plans. We developed indicators for each capacity area to monitor the capacity development.

Through AI, we identified six capacity areas for both municipalities:

- monitoring and evaluation;

- coordination;

- leadership;

- human resources development;

- participation; and

- resource mobilisation.

The CSP staff also conducted training in participatory approaches, such as an awareness-building workshop on participatory learning and action and participatory management. The CSP helped to build the partners’ capacity by:

- training municipality cabinet members and health staff;

- providing on-the-job support for health staff;

- strengthening the health monitoring system;

- training service providers;

- collaborating and networking; and,

- conducting learning visits.

|

| Concern staff review programme activities Photo by: Rezaul Helali |

Designing the programme

The programme plan was developed based on the findings and recommendations of the earlier baseline researches. A series of planning workshops were conducted both in Saidpur and Parbatipur, attended by the municipality cabinet and health staff, representatives from the WHCs, sub district level health staff, CSP staff, and representatives from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. A group process was facilitated to develop the action plan, ensuring that it reflected concerns and recommendations.

Making sure that the socially excluded groups participated in these workshops was very important. CSP staff advised the ward commissioners to have a WHC meeting to select the workshop participants. At the meeting, the ward commissioners acknowledged that they had limited knowledge about the health-related problems of children and mothers from socially excluded groups. So, in order to develop an effective programme plan, the members of the WHCs selected a diverse group of representatives, including socially excluded groups, private service providers, and key community workers.

The programme plan was designed not to introduce any techniques/procedures beyond the capacity of the primary stakeholders. For example, it created a Health Management Information System which relied on existing municipal forms, other service providers’ forms and sub district-level health records. This system collates the major achievements reached jointly by the municipalities and their service providers. It also provides a common ground for better collaboration and sharing of information among them.

A mid-term assessment and sustainability review helped the CSP team to counter-check the overall programme effectiveness and the likelihood of achieving lasting impact. It helped to refocus efforts on key areas of the WHCs’ capacity definitions and building, the coordination of health service providers and the effectiveness of the behaviour change interventions (see Box 1).

Box 1: Sustainability Framework

The Child Survival Technical Support Unit (CSTS) of ORC Macro collaborated with the CORE Group, a membership organisation of over 35 non-governmental organisations managing USAID Child Survival and Health Grants. They initiated a process of developing a common framework for assessing the sustainability of these grants. Through a thorough literature review and key informant interviews, the study revealed that there is no ‘magic bullet’ or single set of steps to achieve sustainability. However, there are a few key areas that improve the probability of succeeding. The three dimensions of the sustainability framework are: primary health goals, organisational and capacity viability, and community and social ecological systems (Sarriot, 2002). The health goal is to contribute to the reduction of maternal and child mortality and morbidity by (a) improving protection of child health through immunisations and environmental sanitation, (b) improving safe motherhood and newborn care, and (c) improving feeding and care practices for young children. The community goal uses WHCs as the main vehicle for strengthening the capacity and competency of the municipality population for sustainable health. The programme goal is that 80% of the WHCs are functional, as per their roles and responsibilities. The institutional capacity goal is to strengthen the municipality health departments’ management, technical skills, and community approach so that it can effectively coordinate and promote health services in the municipality.

Achievements

Changes in the community

|

| Bilikis, the second wife of an absent husband, and her baby survived because of social support from the WHC Photo by: Michelle Kouletio |

All health outcome targets have been surpassed over the past four years. For example, the institutional deliveries increased from 25% in 1999/2000 and nearly doubled in 2003. The immunisation coverage exceeded 75% since 2001. Similarly, the use of antenatal services and seeking appropriate care for sick children escalated.

WHCs have now been established in every ward. A number of them are ready to function independently. WHCs are organising community-level health promotion events. WHCs and the municipality are actively working to improve environmental sanitation, including latrine use and hand washing. The WHC has now become a successful focal point for community mobilisation.

Community health volunteers, most of whom are students, play an important role in raising awareness in the community about health services. They view volunteering as a positive step towards gaining a future career. But the sustainability of the WHCs does not solely depend on volunteers. It also relies on the leadership and political willingness of the ward commissioners and the active involvement of other WHC members. Ward commissioners respond to social pressure from within the community to take a proactive role in leading an effective WHC.

The CSP also understood the importance of the roles played by the traditional birth attendants (TBA), rural medical practitioners, and the other private practitioners (e.g. homeopathic doctors). The CSP developed an innovative approach to the development of their capacity. This involved training to improve their knowledge and technical expertise, developing an effective referral linkage with local health institutions, and establishing a sustainable support network using the WHC. Women with obstetric complications and newborns are now given timely referrals for care. TBAs are also reinforcing the importance of antenatal and postpartum care (during pregnancy and after birth) during home visits. The TBAs benefited from the training, which also improved their reputations as healers and their social standing. The CSP involved local community leaders, imams of the mosques, and teachers with its activities through the WHCs, who worked very closely with the other WHC members. Highly mobilised and motivated, they directly contributed to fundraising through house-to-house appeals to cover health service costs for the very poor. If necessary, they also met with hospital administration staff to negotiate reduced bills for such families.

Changes in the municipality

Health is now one of the most regular and prioritised agenda items for the cabinet members. This is evident from their efforts to increase budgetary allocations for health. In Parbatipur, the annual figure has gone from Taka 15,000 (US$250) for 2000-2001 to Taka 120,000 (US$2,000) in 2004-2005. Cabinet members are actively promoting events such as National Immunisation Days. Ward commissioners are leading their respective WHCs. Increased health staff capacity means more effective healthcare provision. Society’s attitude towards the municipality health department and staff has become much more positive. The attitude of the health staff towards their services has also changed dramatically as a result of increased social acceptance.

Strengthening the Municipality Essential Services Package Coordinating Committees (MESPCC) is one of the priority areas that emerged as tensions developed between an increased community demand for health services and access to quality care. Although MESPCC exists on paper as a government-sanctioned body, there are very few functioning examples. However, with municipality leadership and some external facilitation, the MESPCCs now work towards developing a mutual understanding of the health situation, trust, resource mobilisation, data analysis, and joint priority-setting among private, NGO, government, and informal health service providers. They help focus the provision of quality health services based on the expressed needs of the WHCs and Health Department.

|

Changes within Concern

Other new development partnerships have been initiated following the CSP example. Capacity-building and effective stakeholder participation are now central to all of the programmes. Programme strategies and results are being shared at the national level and Concern is applying learning from the field to advocate for policy changes both at local and national levels.

Chart2

Future challenges

All through its journey, the CSP has faced a number of challenges. Future challenges also remain:

- Since the municipality cabinet consists of democratically elected representatives, there is always the possibility that the cabinet may change, and no longer be willing to endorse CSP activities.

- In a recent circular, the government asked ward commissioners not to participate in MESPCC meetings. This circular was the outcome of the World Health Organization’s GAVI (Global Alliance for Vaccination and Immunization) project. The project advocated that including ward commissioners in the MESPCC increased the size of the committee, which they saw as an obstacle to decision making processes. Concern is trying to get an access to GAVI to understand the implications of this and has already initiated an advocacy programme with the government to withdraw this circular. Concern believes that the participation of the ward commissioners increases the effectiveness of the decision-making process. The best example is that in the last few years, the government opened/relocated many vaccination camps within the sweepers’ colonies, non-Bengali camps, and remote areas on National Immunisation Days because of the strong voice of the ward commissioners in MESPCC.

- Except for the medical officer and the supervisor, the other health department members of staff are considered ‘casual labour’. This makes running the programme difficult, as from their perspective, their ownership is, and is likely to remain, abstract, until they achieve tenured staff status. Once thought of as being minimally qualified and ineffective, with CSP training, they have become effective team members. Until recently, neither municipality had a medical officer. Yet even without a medical officer it is possible to develop a sustainable urban health system. However, without acknowledging the contribution of the health department staff, it will become unsustainable. Concern is now conducting a local-level advocacy programme, and the initial outcomes are positive. The municipal authorities recently increased the monthly salaries of these master roll employees from Taka 700 (US$11.67)/month to Taka 900 (US$15)/month.

- The WHCs have been raising funds to support the poorest mothers. However, any fund mismanagement will endanger the WHCs. Concern has already initiated account management training and is assisting WHCs in opening bank accounts, which will be operated jointly by the ward commissioner and the secretary. Concern is also working closely with WHCs to develop a guideline for spending money from this fund.

|

| Children from Saidpur Photo by: Michelle Kouletio |

Lessons learnt

Concern has gained valuable lessons both from the programme and the organisational perspectives.

Lessons from capacity-building

Capacity-building requires specialised skills in facilitating, negotiating and communicating in participatory and appreciative ways. These skills are different to those needed to implement programmes directly. Concern undertook the CSP while it was shifting from direct implementation to partnership.

Despite promising changes in the capacity areas of the municipalities, Concern inputs were weakened by high turnover of key staff throughout the programme life. Strong technical leaders were promoted to positions which limited their time and scope for guiding the team on the ground. It was difficult to recruit and retain qualified team leaders due to the distance of these sites from the capital city and the nature of qualifications required. These issues resulted in local team leadership gaps for extended periods of time, limiting the overall achievement.

Community and resource mobilisation

Concern has realised that if the community is properly mobilised, and if the messages can be communicated properly to them, they can make anything possible. The effective involvement of several segments of the community in the CSP was helped by various strategies:

- organising meetings (e.g. mothers’ gathering, husbands’ gathering);

- observing national and international days;

- through folk songs and slide shows;

- arranging competitions (e.g. best father competition); and

- awards (e.g. volunteers’ performance reward).

Concern never provided any direct financial inputs either to the municipality authorities or to the community. Our efforts were confined to capacity building inputs. Instead of providing resources, Concern has tried to assist municipalities to identify under-utilised local and national resources that they can have access to.

Reaching more people

This was the first Concern Bangladesh programme to show that partnerships with local government are a very effective way of reaching more people. When Concern was directly providing health services in slum clinics it was only reaching 85,000 people in five different urban areas. Through this partnership CSP now reaches over 200,000 people in the two municipalities, and is preparing to scale-up to seven more municipalities with a total population of over one million. More important is that the latter approach costs much less, is more sustainable and helps to ensure the community’s ownership.

Protection of the very poor

One of the most promising transformations was the increased awareness and support of local leaders to the needs of the very poor and voiceless members of society. They gained a strong understanding of the realities of limited healthcare access among the most vulnerable. Understanding obstacles to reaching hospitals during pregnancy emergencies triggered most of the WHCs to develop special funds and social support mechanisms to reduce these barriers.

Partnership with local government is possible

Partnership with any political institution, especially with local government, is challenging. Local governments do not have sufficient resources. They expect resource endowments from any partnership. They need to be convinced about the benefits of conducting capacity-building over immediate tangible supports, which can often cause conflict between the approaches of programmes like the CSP and the expectations of the partners. However, from the experiences so far, it has been evident that these partnerships can be successful, provided that the right strategies are used.

Differences in success between municipalities

Different levels of success were detected between the two municipalities. Parbatipur is smaller and has a more cohesive population. Participation in the programme was demand driven, and there was strong and consistent municipal leadership. Saidpur also made good progress. However, despite his willingness to participate, the leader’s time was limited because of his competing responsibilities as a national leader. Saidpur municipality’s larger population is much less cohesive with a more diverse ethnic and social composition. Chart 2 shows these differences very clearly in terms of growth in defined capacity areas, which were assessed in 2000 and 2004 based on a set of self-developed indicators.

Final remark: prospects for sustainability

The prospects for sustainability are promising. Health promotion continues. High levels of local ownership and capacity based on local resource availability have been established. The government uses local structures to facilitate the programme’s coordination and participation. National recognition for these achievements and effectiveness has stimulated linkages for ongoing technical support. And several other municipalities have initiated similar processes and strategies by learning directly from Saidpur and Parbatipur.

Over the next five years, the pioneers for municipal health will serve as a Learning Centre, sharing and teaching others, and reinforcing pride and leadership. Yes despite this, how much does the CSP depend on volunteerism? Sceptics argue that once Concern withdraws, the structure developed in the CSP will slowly disintegrate and it is only a matter of time before the municipality will be back to status quo ante. Only time will tell, but there are aspects of the CSP urban health model and its community involvement that offer hope. Young volunteers are effective and dropout is not an issue when there is a community support system. With a high level of community enthusiasm and involvement, students, both women and men, are eager to volunteer and devote up to eight hours a week helping their neighbours on maternal and child health issues. The fact that there are additional youth who work along side and assist the volunteers is even more remarkable. These ‘interns’ are the Community Health Volunteers-in-waiting who will step into the volunteers’ slot if the volunteer gets a paying job, gets married or moves with their family to another location. The volunteers are a positive example of how youth can contribute and use their skills, energy and commitment. In addition, there exists two-way accountability between the community and municipality cabinet members that will go a long way to ensuring that municipal and ward activities continue. Cabinet members cannot ignore the social pressure from the electoral community, which will ultimately force them to take a proactive role in leading an effective WHC.

CONTACT DETAILS

Dipankar Datta

Partnership and Capacity Building Adviser,

Policy Development and Evaluation Directorate,

Concern Worldwide, 52-55 Lower

Camden Street, Dublin 2, Republic of Ireland.

Email: dipankar2kbd@yahoo.com

Michelle Kouletio

Child Survival and Health Adviser, Concern

Worldwide Inc., US, 104 East 40th Street,

Room 903, New York, NY 10016, USA.

Taifur Rahman

Coordinator, Publication & Documentation,

Organisational Development Unit, Concern

Bangladesh, House 58, 1st Lane Kalabagan,

Dhaka 1205, Bangladesh.

REFERENCES

Cooperrider, D L. and Whitney, D. (1999). Appreciative Inquiry: collaboration for change. Berrett-Koehler Communications, Inc. San Francisco.

Sarriot, E. (2002). The Child Survival Sustainability Assessment: for a shared sustainability evaluation methodology in child survival interventions. Child Survival Technical Support project, the Child Survival Collaborations and Resources Group, Calverton, Maryland.

Article citation: “Participatory Learning and Action: Civil society and poverty reduction,” Number 51, April 2005. International Institute for Environment and Development (iied), 3 Endsleigh Street, London WC1HODD, UK

In 2005, Concern Worldwide US Inc. will impact the lives of 8 million people in 18 countries across Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. Concern is also a member of the ONE Campaign, a coalition committed to helping the poorest people in the world overcome AIDS and extreme poverty. For more information, please visit www.concernusa.org.

Concern Worldwide US Inc..is solely responsible for the contents of this article.

Search

Latest articles

Agriculture

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Air Pollution

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Biodiversity

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Desertification

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- UN Food Systems Summit Receives Over 1,200 Ideas to Help Meet Sustainable Development Goals

Endangered Species

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

- Coral Research in Palau offers a “Glimmer of Hope”

Energy

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Wildlife Preservation in Southeast Nova Scotia

Exhibits

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Coral Reefs

Forests

- NASA Satellites Reveal Major Shifts in Global Freshwater Updated June 2020

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Global Climate Change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

Global Health

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- More than 400 schoolgirls, family and teachers rescued from Afghanistan by small coalition

Industry

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Natural Disaster Relief

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

News and Special Reports

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

Oceans, Coral Reefs

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Pollution

- Zakaria Ouedraogo of Burkina Faso Produces Film “Nzoue Fiyen: Water Not Drinkable”

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Population

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Public Health

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Rivers

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Toxic Chemicals

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Actions to Prevent Polluted Drinking Water in the United States

Transportation

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Urbanization Provides Opportunities for Transition to a Green Economy, Says New Report

Waste Management

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water and Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution