Navigation

Accelerating Loss of Ocean Species Threatens Human Well-being

In a study published in the November 3 issue of the journal, Science, an international group of ecologists and economists show that the loss of biodiversity is profoundly reducing the ocean’s ability to produce seafood, resist diseases, filter pollutants, and rebound from stresses such as over fishing and climate change

|

Marine Protected Area, Papua New Guinea.Photo Copyright:ARC COE for Coral Reef Studies/Marine Photobank |

In a study published in the November 3 issue of the journal, Science, an international group of ecologists and economists show that the loss of biodiversity is profoundly reducing the ocean’s ability to produce seafood, resist diseases, filter pollutants, and rebound from stresses such as over fishing and climate change. The study reveals that every species lost causes a faster unraveling of the overall ecosystem. Conversely every species recovered adds significantly to overall productivity and stability of the ecosystem and its ability to withstand stresses.

“Whether we looked at tide pools or studies over the entire world’s ocean, we saw the same picture emerging,” says lead author Boris Worm of Dalhousie University. “In losing species we lose the productivity and stability of entire ecosystems. I was shocked and disturbed by how consistent these trends are - beyond anything we suspected.”

|

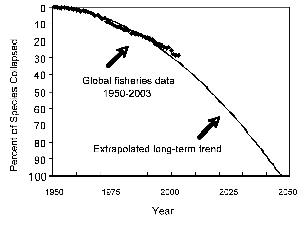

| Fig. 1. Global loss of seafood species. Shown is the current trend in fisheries collapses (data points, based on United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization data base), and extrapolated to 2050 (solid line). |

The four-year analysis is the first to examine all existing data on ocean species and ecosystems, synthesizing historical, experimental, fisheries, and observational datasets to understand the importance of biodiversity at the global scale.

The results reveal global trends that mirror what scientists have observed at smaller scales, and they prove that progressive biodiversity loss not only impairs the ability of oceans to feed a growing human population, but also sabotages the stability of marine environments and their ability to recover from stresses. Every species matters.

“For generations, people have admired the denizens of the sea for their size, ferocity, strength or beauty. But as this study shows, the animals and plants that inhabit the sea are not merely embellishments to be wondered at,” says Callum

|

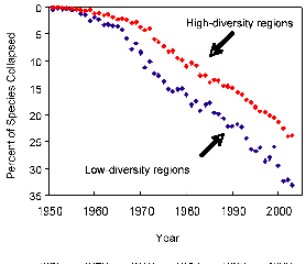

| Fig. 2. Loss of seafood species is faster in low-diversity regions, as compared with high-diversity regions. |

Roberts, a Professor at the University of York, who was not involved in the study. “They are essential to the health of the oceans and the well-being of human society.”

“This analysis provides the best documentation I have ever seen regarding biodiversity’s value,” adds Peter Kareiva, a former Brown University professor and US government fisheries manager who now lead science efforts at The Nature Conservancy. “There is no way the world will protect biodiversity without this type of compelling data demonstrating the economic value of biodiversity.”

The good news is that the data show that ocean ecosystems still hold great ability to rebound. However, the current global trend is a serious concern: it projects the collapse of all species of wild seafood that are currently fished by the year 2050 (collapse is defined as 90% depletion).

Collapses are also hastened by the decline in overall health of the ecosystem – fish rely on the clean water, prey populations and diverse habitats that are linked to higher diversity systems. This points to the need for managers to consider all species together rather than continuing with single species management.

|

| Purse seine tuna boat. Photo Copyright: © Wolcott Henry 2005/Marine Photobank |

“Unless we fundamentally change the way we manage all the oceans species together, as working ecosystems, then this century is the last century of wild seafood,” says co-author Steve Palumbi of Stanford University.

The impacts of species loss go beyond declines in seafood. Human health risks emerge as depleted coastal ecosystems become vulnerable to invasive species, disease outbreaks and noxious algal blooms.

|

| Sea urchins, Maine. Photo Copyright: ARC COE for Coral Reef Studies/Marine Photobank |

Many of the economic activities along our coasts rely on diverse systems and the healthy waters they supply. “The ocean is a great recycler,” explains Palumbi, “It takes sewage and recycles it into nutrients, it scrubs toxins out of the water, and it produces food and turns carbon dioxide into food and oxygen.” But in order to provide these services, the ocean needs all its working parts, the millions of plant and animal species that inhabit the sea.

The strength of the study is the consistent agreement of theory, experiments and observations across widely different scales and ecosystems. The study analyzed 32 controlled experiments, observational studies from 48 marine protected areas, and global catch data from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) database of all fish and invertebrates worldwide from 1950 to 2003. The scientists also looked at a 1000-year time series for 12 coastal regions, drawing on data from archives, fishery records, sediment cores and archeological data.

“We see an accelerating decline in coastal species over the last 1000 years, resulting in the loss of biological filter capacity, nursery habitats, and healthy fisheries,” says co-author Heike Lotze of Dalhousie University who led the historical analysis of Chesapeake Bay, San Francisco Bay, the Bay of Fundy, and the North Sea, among others.

|

| Deep sea catch of Orange Roughy. Photo Copyright: Stephen McGowan/Marine Photobank |

The scientists note that a pressing question for management is whether losses can be reversed. If species have not been pushed too far down, recovery can be fast — but there is also a point of no return as seen with species like northern Atlantic cod.

Examination of protected areas worldwide show that restoration of biodiversity increased productivity four-fold in terms of catch per unit effort and made ecosystems 21% less susceptible to environmental and human caused fluctuations on average.

“The data show us it’s not too late,” says Worm. “We can turn this around. But less than one percent of the global ocean is effectively protected right now. We won’t see complete recovery in one year, but in many cases species come back more quickly than people anticipated — in three to five to ten years. And where this has been done we see immediate economic benefits.”

The buffering impact of species diversity also generates long term insurance values that must be incorporated into future economic valuation and management decisions. “Although there are short-term economic costs associated with preservation of marine biodiversity, over the long term biodiversity conservation and economic development are complementary goals,” says coauthor Ed Barbier, an economist from the University of Wyoming.

|

| Artisanal fishermen haul in their catch. Photo Copyright: ARC COE for Coral Reef Studies/Marine Photobank |

The authors conclude that restoring marine biodiversity through an ecosystem based management approach - including integrated fisheries management, pollution control, maintenance of essential habitats and creation of marine reserves - is essential to avoid serious threats to global food security, coastal water quality and ecosystem stability.

“This isn't predicted to happen, this is happening now,” says co-author Nicola Beaumont an ecological economist with the Plymouth Marine Laboratory. “If biodiversity continues to decline, the marine environment will not be able to sustain our way of life, indeed it may not be able to sustain our lives at all.”

Coastal Study Regions

Drawing on historical data from the last 1000 years, researchers examined ecological changes in the 12 coastal regions the map. Analysis of historical archives, fishery records, sediment cores and archeological studies reveals an accelerating coastal species and a corresponding loss of ecosystem services such as water filtration and fisheries catch.

http://www.fmap.ca//ramweb/media/biodiversity_loss/downloads/coastal_study_regions.pdf

Regional Species Extinctions

Examples of regional species extinctions over the last 1000 years and beyond follows the list of authors below.

###

The study was based at the National Center of Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), funded by the National Science Foundation, the University of California and UC Santa Barbara.

The authors are solely responsible for its contents.

Please contact:

Jessica Brown at jbrown@seaweb.org

Tel: #831-477-2162

http://www.fmap.ca/pressmaterial.php

Author Contact Information:

Boris Worm

Department of Biology Dalhousie University

Phone: 1-902-494-2478

or 1-902-346-2112

Edward B. Barbier

Department of Economics and Finance

University of Wyoming, Laramie

Phone: 1-307-766-2358

Nicola Beaumont

Plymouth Marine Laboratory

Phone: +44-175-263-3423

J. Emmett Duffy

Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences

Phone: 1-804-684-7369

Carl Folke

Department of Systems Ecology

Stockholm University

Phone: +46-816-4217

Benjamin S. Halpern

National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis

Phone: 1-805-892-2531

Jeremy B.C. Jackson

Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Phone: 1-858-822-2790

Cell: 1-858-518-7613

Heike K. Lotze

Department of Biology

Dalhousie University

Phone: 1-902-494-3406

Fiorenza Micheli

Hopkins Marine Station

Stanford University

Phone: 1-831-655-6250

Cell: 1-831-917-7903

Stephen R. Palumbi

Hopkins Marine Station

Stanford University

Phone: 1-831-655-6210

Enric Sala

Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Phone: 1-858-822-2790

Kimberley A. Selkoe

National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis

Phone: 1-805-892-2531

John J. Stachowicz

Section of Evolution and Ecology

University of California, Davis

Phone: 1-530-752-1113

Cell: 1-530-867-2138

Reg Watson

Fisheries Centre

University of British Columbia

Cell: +61-042-401-9503

(Note: This is at GMT+11, in Hobart, Australia)

Regional Species Extinctions

Examples of regional species extinctions over the last 1000 years and beyond.

Region | Species Extinctions |

Baltic Sea

| Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus)* Right whale (Eubalaena glacialis)* Bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) Swordfish (Xiphias gladius)* European sturgeon (Acipenser sturio) Dalmatian pelican (Pelecanus crispus) Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) |

Northern Adriatic Sea

| Monk seal (Monachus monachus) Angular rough shark (Oxynotus centrina) Soupfin shark (Galeorhinus galeus) Sharpnore seven gill shark (Heptranchias brucus) Sandy ray (Leucoraja circularis) White skate (Dipturus alba) Common skate (Dipturus batis) Dusky grouper (Epinephelus marginatis) |

Wadden Sea, southern North Sea

| Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus)* Right whale (Eubalaena glacialis)* Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)§ Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) § European sturgeon (Acipenser sturio) Atlantic shad (Alosa alosa) § Sea trout (Salmo trutta) § Houting (Coregonus oxyrhynchus) § Dalmatian pelican (Pelecanus crispus)* Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber)* Squacco heron (Ardeola ralloides) Roseate tern (Sterna dougallii) Caspian tern (Sterna caspia) Great snipe (Gallinago media) European oyster (Ostrea edulis) § Lacuna snail (Lacuna vincta) |

Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence

| Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus)* Right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) Atlantic walrus (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) Sea mink (Mustela macrodon) Labrador duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius) Great auk (Pinguinus impennis) Eelgrass limpet (Lottia alveus) |

Outer Bay of Fundy

| Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus)* Sea mink (Mustela macrodon) Striped bass, St. John River, (Morone saxatilis) Atlantic salmon, St. Croix River (Salmo salar) § Labrador duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius) Great auk (Pinguinus impennis) Eelgrass limpet (Lottia alveus) |

Massachusetts Bay

| Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) Sea mink (Mustela macrodon) |

Delaware Bay

| Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) §

|

Chesapeake Bay

| Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) §

|

Pamlico Sound

| Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) |

* Unclear how abundant these species were in former times

§ Extinct or nearly extinct breeding population

Search

Latest articles

Agriculture

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Air Pollution

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Biodiversity

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Desertification

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- UN Food Systems Summit Receives Over 1,200 Ideas to Help Meet Sustainable Development Goals

Endangered Species

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

- Coral Research in Palau offers a “Glimmer of Hope”

Energy

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Wildlife Preservation in Southeast Nova Scotia

Exhibits

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Coral Reefs

Forests

- NASA Satellites Reveal Major Shifts in Global Freshwater Updated June 2020

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Global Climate Change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

Global Health

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- More than 400 schoolgirls, family and teachers rescued from Afghanistan by small coalition

Industry

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Natural Disaster Relief

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

News and Special Reports

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

Oceans, Coral Reefs

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Pollution

- Zakaria Ouedraogo of Burkina Faso Produces Film “Nzoue Fiyen: Water Not Drinkable”

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Population

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Public Health

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Rivers

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Toxic Chemicals

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Actions to Prevent Polluted Drinking Water in the United States

Transportation

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Urbanization Provides Opportunities for Transition to a Green Economy, Says New Report

Waste Management

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water and Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution