Navigation

Millions of Jellyfish in Jellyfish Lake Found to “Biomix,” Churning Nutrients of the Lake

"Biomixing" by floating animals churns waters in oceans, seas, lakes: Through this process, jellyfish and other zooplankton--where they're abundant, as they are in Jellyfish Lake--may in some way affect Earth's climate.

|

| A view of Jellyfish Lake, with golden jellyfish following the sun across a wind-rippled surface. Credit: Michael Dawson, UC-Merced |

"Biomixing" by floating animals churns waters in oceans, seas, lakes: Through this process, jellyfish and other zooplankton--where they're abundant, as they are in Jellyfish Lake--may in some way affect Earth's climate. "Biomixing may be a form of 'ecosystem engineering' by jellyfish, and a major contributor to carbon sequestration, especially in semi-enclosed coastal waters," says marine scientist Michael Dawson.

If you were to snorkel just before dawn at the popular tropical Pacific destination Jellyfish Lake, you'd have lots of company: millions of golden jellyfish, known to scientists as Mastigias papua, mill around the western half of the lake, waiting for sunrise.

|

| Aerial view of Jellyfish Lake on the island of Eil Malk in Palau. This view is looking west across the lake. Cropped and colour-corrected from the original. Photo: Wikipedia |

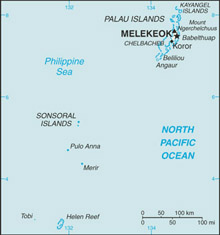

With the sun's first rays, Jellyfish Lake, located 550 miles east of the Philippines in the island nation of Palau, comes alive. As the sky brightens in the east, the golden jellies turn and swim toward a solar beacon.

The jellies need sunlight to sustain algae-like zooxanthellae within their tissues; the zooxanthellae in turn help to sustain the jellies. The Mastigias also get their nourishment from eating copepods and fish larvae among other creatures.

For several hours the jellyfish swim, the contractions of their bells never stopping, until they approach the eastern end of the lake.

Following the rising sun, the jellyfish are stopped, not by the edge of the lake, but by shadows cast by overhanging trees which they meticulously avoid.

Millions of jellyfish that started out in the west are now densely packed around the illuminated eastern rim of the lake. For a few hours around noon, they're stationary, basking in the mid-day sun directly overhead.

Later in the afternoon the jellies swim westward following the sun.

Eventually the jellyfish complete one round-trip migration from west to east and back, each day between sunrise and sunset.

What the jellies are doing, say marine scientists Michael Dawson of the University of California at Merced and John Dabiri of the California Institute of Technology, is "biomixing"--as they swim, they're churning and churning the waters and nutrients of the lake.

|

| One jellyfish "portrait" among millions, in the turquoise-blue waters of Jellyfish Lake. |

Jellyfish like Mastigias papua and the moon jelly Aurelia aurita use their body motion, Dawson and Dabiri have found, to generate water flow that transports small copepods within feeding range. "The 'underwater turbulence' the jellies create is being debated as a major player in ocean energy budgets," says Dabiri.

Dr. John Costello of Providence College, who is working with Dawson and Dabiri on this issue in Palau, has been doing work on how flow affects prey capture for many years.

Dabiri and Dawson are investigating whether biomixing could be responsible for an important part of how ocean, sea and lake waters form eddies, or ring-shaped currents, which bring nitrogen, carbon and other elements from one part of a water body to another.

Through this process, jellyfish and other zooplankton--where they're abundant, as they are in Jellyfish Lake--may in some way affect Earth's climate.

"Biomixing may be a form of 'ecosystem engineering' by jellyfish, and a major contributor to carbon sequestration, especially in semi-enclosed coastal waters," says Dawson.

|

| A weather station monitors conditions at Jellyfish Lake. The surface area of the lake is about 50,000 sq. m and its maximum length is about a half-kilometer. Its maximum depth is about 30 m. Credit: Mike Dawson, University of California at Merced |

With funding from the NSF's Division of Ocean Sciences, Dawson and Dabiri are analyzing biomixing. Among other instruments, they use SCUVA--Self-Contained Underwater Velocimetry Apparatus--to measure water flow around jellyfish.

"Applications of new technology allow us to see how processes actually occur in nature," says David Garrison, director of NSF's Biological Oceanography Program, which funded the research. "Results from this study may change some of our long-held conceptions about mixing processes in the oceans."

The view of jellyfish as passive drifters-in-the-currents may need revision, says Cynthia Suchman of NSF's Biological Oceanography Program.

|

| Jellyfish Lake is one of 70 such saltwater lakes in the Pacific islands. Credit: FAA |

Jellyfish Lake, known to Palauans as Ongeim'l Tketau (for unknown reasons, "fifth lake"), is one of more than 70 saltwater lakes in the Pacific islands. It is a tidal lake entirely surrounded by land but it is connected to the ocean via tunnels in the surrounding islands (karst).

Dawson said, “ The thing we don't know for sure is whether water did (and does) flow all the way from the ocean to the lake, and vice versa, on a single tidal cycle, or whether the distance is too far for this level of immediate exchange. This is one of the things we need to quantify as part of this project.”

At night, the jellies descend to a bottom-layer of hydrogen sulfide.

Although snorkeling in the surface waters of the lake is allowed, SCUBA diving is prohibited to avoid disturbing the jellyfish, and to reduce the risk of hydrogen sulfide poisoning.

|

| Scientist Kakani Young of Caltech uses a new particle image system in Jellyfish Lake in Palau. |

In December, 1998, Jellyfish Lake's population of Mastigias papua, which usually numbers more than 10 million, disappeared completely. The lake temperature increased several degrees following the 1997-98 El Niño.

Then in 2001, the lake cooled, a new generation of jellyfish strobilated (reproduced in an asexual reproductive method specific to the true jellyfish), and there has been no comparable increase in temperature--or lack of jellyfish--since.

While scientists search for answers, golden jellyfish continue their age-old west-to-east-and-back-again migration, ever seeking the sun.

Investigator Michael Dawson, University of California – Merced contributed to this article with other content from a National Science Foundation release of May 8, 2009.

Investigators

John Dabiri, California Institute of Technology

Michael Dawson, University of California - Merced

Search

Latest articles

Agriculture

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Air Pollution

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Biodiversity

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Desertification

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- UN Food Systems Summit Receives Over 1,200 Ideas to Help Meet Sustainable Development Goals

Endangered Species

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

- Coral Research in Palau offers a “Glimmer of Hope”

Energy

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Wildlife Preservation in Southeast Nova Scotia

Exhibits

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Coral Reefs

Forests

- NASA Satellites Reveal Major Shifts in Global Freshwater Updated June 2020

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Global Climate Change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

Global Health

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- More than 400 schoolgirls, family and teachers rescued from Afghanistan by small coalition

Industry

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Natural Disaster Relief

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

News and Special Reports

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

Oceans, Coral Reefs

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Pollution

- Zakaria Ouedraogo of Burkina Faso Produces Film “Nzoue Fiyen: Water Not Drinkable”

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Population

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Public Health

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Rivers

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Toxic Chemicals

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Actions to Prevent Polluted Drinking Water in the United States

Transportation

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Urbanization Provides Opportunities for Transition to a Green Economy, Says New Report

Waste Management

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water and Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution