Navigation

Guidance for Applying the One Health Approach to Enhance Prevention and Curative Care for Humans and Animals

- avian influenza

- brucellosis

- clinical

- environmental health

- harmful algal blooms

- health risks

- integrated pest management

- IPM

- malaria

- One Health

- pets

- public health

- reverse zoonosis or anthroponosis

- toxicants

- veterinary medicine

- wildlife

- zoonoses

- Global Health

- Population

- Public Health

- Sanitation

- Toxic Chemicals

- Water

- Water and Sanitation

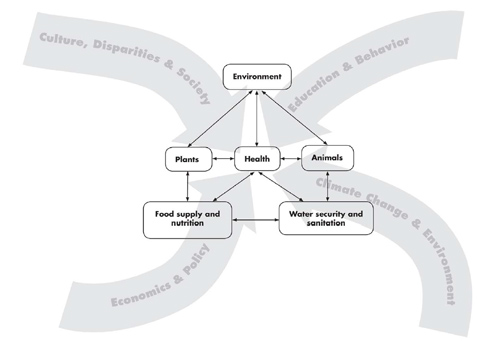

SARS, coronavirus, antibiotic resistant bacteria, Lyme disease, West Nile Virus, lead poisoning, pesticides, disease reservoirs, and environmental conditions are just a few of the concerns and factors addressed in the transdisciplinary “One Health” approaches to enhance prevention and therapeutic care for humans and animals discussed in the book, Human-Animal Medicine: Clinical Approaches to Zoonoses, Toxicants and Other Shared Health Risks. This timely, valuable book by Doctors Peter M. Rabinowitz and Lisa A. Conti, along with many other authors, provides insights and guidance while calling for greater cooperation among human health and veterinary care providers.

Dog washing: Keeping your furry pets healthy includes keeping them clean, as well.: Together, this family was in the process of washing their Labrador retriever outside in the fresh air. The mother, young daughter and son, were soaping down the dog’s coat, while the father was steadying the pet using a leash and his hand. By washing down his coat, chances for the animal to bring contaminants indoors, is highly reduced. After returning from the outdoors, pets can bring allergens, disease vectors such as ticks and fleas, and pathogens from other animals indoors, thereby exposing the entire family to these dangers. One should remember to wash his/her hands after finishing this activity. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA). Image by CDC/ Dawn Arlotta

Dog washing: Keeping your furry pets healthy includes keeping them clean, as well.: Together, this family was in the process of washing their Labrador retriever outside in the fresh air. The mother, young daughter and son, were soaping down the dog’s coat, while the father was steadying the pet using a leash and his hand. By washing down his coat, chances for the animal to bring contaminants indoors, is highly reduced. After returning from the outdoors, pets can bring allergens, disease vectors such as ticks and fleas, and pathogens from other animals indoors, thereby exposing the entire family to these dangers. One should remember to wash his/her hands after finishing this activity. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA). Image by CDC/ Dawn Arlotta

SARS, coronavirus, antibiotic resistant bacteria, Lyme disease, West Nile Virus, lead poisoning, pesticides, disease reservoirs, and environmental conditions are just a few of the concerns and factors addressed in the transdisciplinary “One Health” approaches to enhance prevention and therapeutic care for humans and animals discussed in the book, Human-Animal Medicine: Clinical Approaches to Zoonoses, Toxicants and Other Shared Health Risks. This timely, valuable book by Doctors Peter M. Rabinowitz and Lisa A. Conti, along with many other authors, provides insights and guidance while calling for greater cooperation among human health and veterinary care providers.

“Carbon monoxide (CO) is the most common cause of poisoning-related death,” write Rabinowitz and Conti.: “Because the gas has no warning odor or color and the symptoms are often subtle and nonspecific…. CO is an example of a toxicant for which companion animals could provide early of human exposure risk.” Seen here is a domestic canary, of the type historically used to detect gas in coal mines. Animals as “sentinels” of environmental health hazards are presented in The Yale Human Animal Medicine Project Canary Database available at http://www.canarydatabase.org. Photograph courtesy of Wikipedia.

“Carbon monoxide (CO) is the most common cause of poisoning-related death,” write Rabinowitz and Conti.: “Because the gas has no warning odor or color and the symptoms are often subtle and nonspecific…. CO is an example of a toxicant for which companion animals could provide early of human exposure risk.” Seen here is a domestic canary, of the type historically used to detect gas in coal mines. Animals as “sentinels” of environmental health hazards are presented in The Yale Human Animal Medicine Project Canary Database available at http://www.canarydatabase.org. Photograph courtesy of Wikipedia.

From our early childhood, most of us have heard of lovely little canaries being taken down into mines to act as sentinels, “watchmen” warning of danger. “Canaries were found to be more sensitive than human beings to the toxic effects of carbon monoxide and methane gas in coal mines, allowing them to provide early warning to miners if they began to act sick,” the authors write in Human-Animal Medicine.

“Physiological differences in metabolism in some animals may make them more sensitive than human beings to some toxicants,” they explain. “Rocky Mountain spotted fever in dogs has led to the discovery and treatment of disease in a human patient; …a dog that becomes ill after ingesting toxic berries on an ornamental plant signals a potential danger for children who could inadvertently ingest the berries; and, Elevated blood lead levels in pets are an indicator of lead exposure risk in children nearby.”

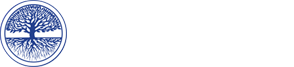

The local and global influences impacting human health, including the interdependence of people, animals, plants , and: the environment, and the associated food and water availability, safety, and security. Graphic artist credit: A. Kent. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000190.g001 PLoS Med 6(12): e1000190.

The local and global influences impacting human health, including the interdependence of people, animals, plants , and: the environment, and the associated food and water availability, safety, and security. Graphic artist credit: A. Kent. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000190.g001 PLoS Med 6(12): e1000190.

In the United States cattle are checked yearly for brucellosis, an infectious disease in humans and other animals that is caused by bacteria.

Brucellosis: This image depicts a sow with her new litter of piglets. Some of the newborn are dead, and others are sickly due to: a case of brucellosis, caused by the bacterium, Brucella suis. Swine brucellosis causes abortion, reduced milk production, and infertility. People can get the disease when they are in contact with infected animals or animal products contaminated with the bacteria. Animals that are most commonly infected include sheep, cattle, goats, pigs, and dogs, among others. The most common way to be infected is by eating or drinking unpasteurized/raw dairy products. When sheep, goats, cows, or camels are infected, their milk becomes contaminated with the bacteria. If the milk from infected animals is not pasteurized, the infection will be transmitted to people who consume the milk and/or cheese products. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA)

Brucellosis: This image depicts a sow with her new litter of piglets. Some of the newborn are dead, and others are sickly due to: a case of brucellosis, caused by the bacterium, Brucella suis. Swine brucellosis causes abortion, reduced milk production, and infertility. People can get the disease when they are in contact with infected animals or animal products contaminated with the bacteria. Animals that are most commonly infected include sheep, cattle, goats, pigs, and dogs, among others. The most common way to be infected is by eating or drinking unpasteurized/raw dairy products. When sheep, goats, cows, or camels are infected, their milk becomes contaminated with the bacteria. If the milk from infected animals is not pasteurized, the infection will be transmitted to people who consume the milk and/or cheese products. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA)

“Worldwide, brucellosis is considered largely an occupational disease of workers exposed to cattle and other large animals through animal husbandry, dairy, and slaughter operations. Such workers include herdsmen, slaughterhouse workers, and veterinarians...another risk is sharing living spaces with potentially infected animals; high rates of brucellosis have been reported among goat-herding families that bring goats into family bedrooms during the winter.”

This quote about brucellosis is from Human-Animal Medicine, a well-conceived and well-written compendium of comprehensive, amply illustrated chapters designed to help clinicians and pubic health officials “manage a range of clinical problems at the intersection of human and animal health.”

Human-Animal Medicine BookThe book seeks to “bridge the gaps between human and animal health” with its chapters constructed to show similarities and differences between human and animal diseases. With extensive charts, tables, and figures it conveys “Key Points for Clinicians and Public Health Professionals,” for diagnosis and preventive measures, about toxicity and treatment measures, and other considerations.

Human-Animal Medicine BookThe book seeks to “bridge the gaps between human and animal health” with its chapters constructed to show similarities and differences between human and animal diseases. With extensive charts, tables, and figures it conveys “Key Points for Clinicians and Public Health Professionals,” for diagnosis and preventive measures, about toxicity and treatment measures, and other considerations.

For example, the chapter “Toxic Exposures,” by Rabinowitz and Conti, provides the reader with basic considerations of what is important to keep a home safe “in terms of toxic hazards such as carbon monoxide and pesticides.”

They write, “this concept [of a healthy home] is one in which human health care providers, public health professionals, and veterinarians can actively collaborate because it seems clear that what is good for human beings in the household in terms of toxic hazard reduction is also good for animals living in the household.”

The chapter summarizes guidelines, or key points. For example, for public health professionals, they advise educating the public on principles for a safer, healthier home that includes eliminating tobacco smoke and toxic substances and using integrated pest management (IPM) techniques for rodent, weed and insect control. “IPM is a commonsense and environmentally sensitive approach to pest management that uses current, comprehensive information on the life cycle of pests and their interaction with the environment.”

For human health and veterinary clinicians, they counsel consideration of toxic exposures in the differential diagnosis of both acute and chronic medical problems and animal illnesses.

“Six years before the detection of Minamata disease, an outbreak of severe methyl mercury poisoning among families living near Minamata Harbor in Japan, strange clinical signs were seen in local cats that ate diets high in fish from the bay. This ‘dancing cat disease’ included twitching, spasms, abnormal movements, and convulsions. Only later was the association made between the neurological signs in the cats and the devastating signs of mercury poisoning in children and adults (who also ate mercury-contaminated fish from the bay) that included mental retardation, seizures, and other neurological damage.”

This striking example and other animal-human connections of toxic substance exposure was studied by a National Academy of Sciences panel that concluded, as reported in this book, “that domestic animals and wildlife could serve as useful sentinels of human environmental hazards because they may develop recognizable signs or biomarkers of toxicity in a timely way to provide a warning to human beings and to assist in human risk assessment.”

“At times, an unusual cluster of disease in an animal population may suffice to draw attention to a particular hazard. For example, when horses (and dogs) in Times Beach, Missouri, began to die after their stable area was sprayed with oil to control dust, it was discovered that the oil was contaminated with dioxin.”

Among the toxic substances addressed are foods toxic to companion animals, common medications and their toxicity in humans and animals, poisonous plant exposure, and cleaning products.

Pedanius Dioscorides (c40-c90AD) noted lead's effect on the mind in the first century A.D.: Photograph courtesy of Wikipedia.

Pedanius Dioscorides (c40-c90AD) noted lead's effect on the mind in the first century A.D.: Photograph courtesy of Wikipedia.

Vivid pictures compare a heifer and an iguana exposed to lead.

An accompanying table outlines differences and similarities in species and covers risk factors, toxic levels, clinical manifestations, and laboratory findings.

For example, while children’s clinical manifestations are listed as learning problems, confusion, seizures and renal dysfunction, cattle and horses’ manifestations include anorexia, colic, constipation, ataxia, muscle tremors, and convulsions, reptiles’ manifestations are listed as abnormal behavior, weakness, and gait difficulties.

"A zoonosis (pron.: /ˌzoʊ.əˈnoʊsɨs/) (also spelled zoönosis) is an infectious disease that is transmitted between species (sometimes by a vector) from animals other than humans to humans or from humans to other animals (the latter is sometimes called reverse zoonosis or anthroponosis). In direct zoonosis the agent needs only one host for completion of its life cycle, without a significant change during transmission.

This definition is from Wikipedia from "Zoonosis". Medical Dictionary. Retrieved 2013-01-30.

A major section of the book, also written by Rabinowitz and Conti, is on “Zoonoses.” “The history of contact between animals and humans has always involved infectious diseases, and today more than half of the infectious diseases of humans are zoonotic in origin,” they write. “In fact, the majority of ‘emerging’ infectious diseases in the past three decades are zoonotic. Therefore the control and prevention of these diseases can be accomplished only through improving approaches to reducing disease transmission among humans and other animals.”

Examples given are severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), West Nile virus, monkeypox, and avian influenza. The authors observe that “despite the great deal of attention that has been focused on emerging diseases attention [on such] emerging infectious zoonotic diseases,” there has been “less discussion and effort targeted at the environmental ‘drivers’ of such diseases.”

“For many zoonotic diseases,” they emphasize, measures involving controlling animal reservoirs, such as by culling, and using personal protection or pesticides for vector control are limited approaches because “the ultimate causes of infection in the animals may not be addressed sufficiently.

"For example, Nipah virus emerged as a deadly pathogen in Malaysia when pig farms were built close to forest areas frequented by fruit bats.

Bats and Nipah virus:Though their specie is unknown, this image depicts numerous flying foxes of the genus Pteropus,: which were hanging up-side-down from the trees in their resting position. The natural reservoir for Hendra virus is thought to be flying foxes (bats of the genus Pteropus) found in Australia. The natural reservoir for Nipah virus is still under investigation, but preliminary data suggest that bats of the genus Pteropus are also the reservoirs for Nipah virus in Malaysia. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA).

Bats and Nipah virus:Though their specie is unknown, this image depicts numerous flying foxes of the genus Pteropus,: which were hanging up-side-down from the trees in their resting position. The natural reservoir for Hendra virus is thought to be flying foxes (bats of the genus Pteropus) found in Australia. The natural reservoir for Nipah virus is still under investigation, but preliminary data suggest that bats of the genus Pteropus are also the reservoirs for Nipah virus in Malaysia. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA).

Pig farm in Malaysia, 1999.: In Australia, humans became ill after exposure to body fluids and excretions of horses infected with Hendra virus. In Malaysia and Singapore, humans were infected with Nipah virus through close contact with infected pigs. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA)

Pig farm in Malaysia, 1999.: In Australia, humans became ill after exposure to body fluids and excretions of horses infected with Hendra virus. In Malaysia and Singapore, humans were infected with Nipah virus through close contact with infected pigs. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA)

"These fruit bats, natural hosts for Nipah and other henipaviruses, had sufficient contact with pig farms to allow the virus pathogen to ‘spill over’ from the wildlife reservoir into the domestic pig population, causing mortality for pigs and humans (and cats) in contact with them.”

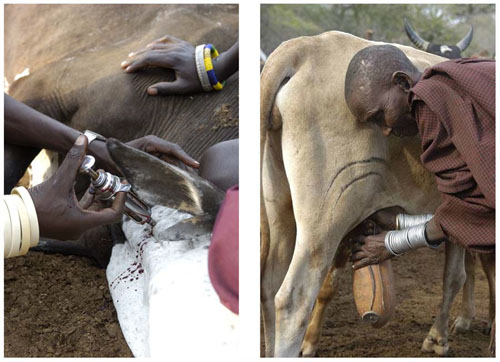

Men’s and women’s disease risks from livestock likely differ: men have occasional, but intense contact: with sick animals (left), while women have regular, close contact with animals, particularly poultry and lactating cows and goats (right). Photograph courtesy of M. Kock-Wildlife Conservation Society. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000190.g003 Courtesy of PLoS Med 6(12): e1000190.

Men’s and women’s disease risks from livestock likely differ: men have occasional, but intense contact: with sick animals (left), while women have regular, close contact with animals, particularly poultry and lactating cows and goats (right). Photograph courtesy of M. Kock-Wildlife Conservation Society. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000190.g003 Courtesy of PLoS Med 6(12): e1000190.

“Every day thousands of children and adults die from underdiagnosed diseases that have arisen at the human–animal–environment interface, especially diarrheal and respiratory diseases in developing countries1, 2,” according to the article ‘‘A ‘One Health’ Approach to Address Emerging Zoonoses: The HALI Project in Tanzania”* “An important implication of the One Health approach is that integrated policy interventions that simultaneously and holistically address multiple and interacting causes of poor human health — unsafe and scarce water, lack of sanitation, food insecurity, and close proximity between animals and humans — will yield significantly larger health benefits than policies that target each of these factors individually and in isolation.”

“Explosive human population growth and environmental changes have resulted in increased numbers of people living in close contact with wild and domestic animals. Unfortunately, this increased contact together with changes in land use, including livestock grazing and crop production, have altered the inherent ecological balance between pathogens and their human and animal hosts.

“In fact, zoonotic pathogens, such as influenza and SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), account for the majority of emerging infectious diseases in people3, and more than three-quarters of emerging zoonoses are the result of wildlife-origin pathogens4.”

Banded mongoose share the Botswana landscape with humans; leptospirosis often follows.: Photograph courtesy of B. Fairbanks, Virginia Tech

Banded mongoose share the Botswana landscape with humans; leptospirosis often follows.: Photograph courtesy of B. Fairbanks, Virginia Tech

“Human Disease Leptospirosis Identified in New Species, the Banded Mongoose, in Africa: Scientists find widespread but neglected disease is significant health threat in Botswana,” reported the National Science Foundation (NSF) on May 14, 2013, on the findings Kathleen Alexander, Sarah Jobbins and Claire Sanderson of Virginia Tech published in the journal Zoonoses and Public Health.

The newest public health threat in Africa, scientists have found, is coming from a previously unknown source: the banded mongoose. Leptospirosis, the disease is called. And the banded mongoose carries it. Leptospirosis is the world's most common illness transmitted to humans by animals. It's a two-phase disease that begins with flu-like symptoms. If untreated, it can cause meningitis, liver damage, pulmonary hemorrhage, renal failure and death.

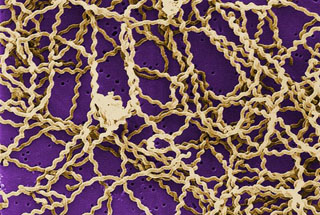

Leptospires are long, thin motile spirochetes that may be free-living or associated with animal hosts and: survive well in fresh water, soil, and mud in tropical areas. Organisms are antigenically complex, with over 200 known pathogenic serologic variants. Molecular taxonomic studies at CDC and elsewhere have identified 13 named and 4 unnamed species of pathogenic leptospires. Leptospirosis causes a wide range of symptoms, and some infected persons may have no symptoms at all. Symptoms of leptospirosis include high fever, severe headache, chills, muscle aches, and vomiting, and may include jaundice (yellow skin and eyes), red eyes, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or a rash. This scanning electron micrograph (SEM) depicts a number of Leptospira sp. bacteria atop a 0.1. µm polycarbonate filter. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA).In Human-Animal Medicine, leptospirosis, discussed in the extensive chapter “Zoonoses,” is presented with key points for public health professionals, human health clinicians, and veterinary clinicians for prevention and control. It provides information about the causative agent, a gram-negative spirochete bacteria in the genus Leptospira, about the extensive geographic occurrence, “Leptospirosis is considered an emerging infectious disease and one of the most common global zoonoses: it is found worldwide except in the polar regions…” and about the groups at risk, among pertinent details. These include hosts, reservoir species, vectors, and environmental risk factors.

Leptospires are long, thin motile spirochetes that may be free-living or associated with animal hosts and: survive well in fresh water, soil, and mud in tropical areas. Organisms are antigenically complex, with over 200 known pathogenic serologic variants. Molecular taxonomic studies at CDC and elsewhere have identified 13 named and 4 unnamed species of pathogenic leptospires. Leptospirosis causes a wide range of symptoms, and some infected persons may have no symptoms at all. Symptoms of leptospirosis include high fever, severe headache, chills, muscle aches, and vomiting, and may include jaundice (yellow skin and eyes), red eyes, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or a rash. This scanning electron micrograph (SEM) depicts a number of Leptospira sp. bacteria atop a 0.1. µm polycarbonate filter. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA).In Human-Animal Medicine, leptospirosis, discussed in the extensive chapter “Zoonoses,” is presented with key points for public health professionals, human health clinicians, and veterinary clinicians for prevention and control. It provides information about the causative agent, a gram-negative spirochete bacteria in the genus Leptospira, about the extensive geographic occurrence, “Leptospirosis is considered an emerging infectious disease and one of the most common global zoonoses: it is found worldwide except in the polar regions…” and about the groups at risk, among pertinent details. These include hosts, reservoir species, vectors, and environmental risk factors.

This and each other section in the chapter includes pertinent information on environmental aspects of a clinical problem involving human and animal health, and how water can play an important role. Environmental risk factors for leptospirosis are cited: “Outbreaks in humans and animals have been linked to heavy rains resulting in flooding, moist soils, and standing water.”

“Leptospirosis is an important occupational disease risk for farmers, dairy and abattoir (slaughterhouse) workers, butchers, hunters, dog handlers, veterinarians, and other veterinary health providers who have direct contact with animals. Workers with exposure to contaminated water, such as military personnel, rice farmers, fishing industry workers, plumbers, and sewage workers, are also at risk.”

The significance of water and natural resource limitations are addressed in, ‘‘A ‘One Health’ Approach to Address Emerging Zoonoses… ”: “Nowhere in the world are these health impacts more important than in developing countries, where daily workloads are highly dependent on the availability of natural resources6,7,” the authors write. “Water resources are perhaps most crucial, as humans and animals depend on safe water for health and survival, and sources of clean water are dwindling due to demands from agriculture and global climate change.

“As water becomes more scarce, animals and people are squeezed into smaller and smaller workable areas. Contact among infected animals and people then increases, facilitating disease transmission.

“Water scarcity also means that people and animals use the same water sources for drinking and bathing, which results in serious contamination of drinking water and increased risk of zoonotic diseases.

“In addition, poor sanitation and animal management can result in fecal contamination of both animal and human food. When this situation is complicated by high HIV/AIDS prevalence, the impacts of otherwise minimally virulent or difficult-to-transmit pathogens can be catastrophic to families and entire communities, and ultimately to the environment through impacts on human capacity, natural resource management, and land use8.”

In “Zoonoses,” a shared risk approach is presented for a number of zoonotic diseases. “For each disease, environmental risk factors (drivers) of infectious risk are discussed, as well as practical steps that public health, human health, and animal health professionals can take to prevent, control, diagnose, and treat such infections. A key step with each disease is providing accurate information about risk to clients and other members of the health professions.”

Many experts in addition to Rabinowitz and Conti wrote this extensive chapter and other chapters. Among them, Julia Zaias, DVM, PhD, Research Assistant Professor, Comparative Pathology, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Lora E Fleming, MD, PhD, Professor and Director, European Centre for Environment and Human Health, University of Exeter Medical School, and Lorraine C. Backer, PhD, MPH, Team Leader for the National Center for Environmental Health of the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention, who co-authored the Human-Animal Medicine chapter, “Harmful Algal Blooms [HABs].”

Toxic Algae Bloom in Lake Erie: The green scum shown in this image, taken in October 2011,is the worst algae: bloom Lake Erie has experienced in decades. Such blooms were common in the lake’s shallow western basin in the 1950s and 60s. Phosphorus from farms, sewage, and industry fertilized the waters so that huge algae blooms developed year after year. The blooms subsided a bit starting in the 1970s, when regulations and improvements in agriculture and sewage treatment limited the amount of phosphorus that reached the lake. But in 2011, a giant bloom spread across the western basin once again. The reasons for the bloom are complex, but may be related to a rainy spring and invasive mussels. Vibrant green filaments extend out from the northern shore. The bloom is primarily microcystis aeruginosa, an algae that is toxic to mammals, according to the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory. Several days of calm winds and warm temperatures allowed the algae to gather on the surface. Microcystis aeruginosa produces a liver toxin, microcystin, that commonly kills dogs swimming in infected water and causes skin irritation for people. Richard Stumpf, an oceanographer with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, measured 50 times more microcystin in Lake Erie in the summer of 2011 than the World Health Organization recommends for safe recreation. Though not directly toxic to fish, the bloom is not good for marine life. After the algae dies, bacteria break it down. The decay process consumes oxygen, so the decay of a large bloom can leave “dead zones,” low oxygen areas where fish can’t survive. If ingested, the algae can cause flu-like symptoms in people and death in pets. Photograph and text courtesy of NASA

Toxic Algae Bloom in Lake Erie: The green scum shown in this image, taken in October 2011,is the worst algae: bloom Lake Erie has experienced in decades. Such blooms were common in the lake’s shallow western basin in the 1950s and 60s. Phosphorus from farms, sewage, and industry fertilized the waters so that huge algae blooms developed year after year. The blooms subsided a bit starting in the 1970s, when regulations and improvements in agriculture and sewage treatment limited the amount of phosphorus that reached the lake. But in 2011, a giant bloom spread across the western basin once again. The reasons for the bloom are complex, but may be related to a rainy spring and invasive mussels. Vibrant green filaments extend out from the northern shore. The bloom is primarily microcystis aeruginosa, an algae that is toxic to mammals, according to the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory. Several days of calm winds and warm temperatures allowed the algae to gather on the surface. Microcystis aeruginosa produces a liver toxin, microcystin, that commonly kills dogs swimming in infected water and causes skin irritation for people. Richard Stumpf, an oceanographer with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, measured 50 times more microcystin in Lake Erie in the summer of 2011 than the World Health Organization recommends for safe recreation. Though not directly toxic to fish, the bloom is not good for marine life. After the algae dies, bacteria break it down. The decay process consumes oxygen, so the decay of a large bloom can leave “dead zones,” low oxygen areas where fish can’t survive. If ingested, the algae can cause flu-like symptoms in people and death in pets. Photograph and text courtesy of NASA

I choose to mention the “Harmful Algal Blooms” chapter both because of the significance of the subject and because Fleming and Backer, also addressed HABs in the chapter they co-authored with others, “Naturally Occurring Water Pollutants,” in Horizon International’s book, Water and Sanitation Related Diseases and the Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures, for which I was Editor.

As they write in Human-Animal Medicine, “Although it has been known for decades, if not centuries, that exposure to certain HAB toxins causes adverse health effects, studies designed to more fully characterize these acute and chronic effects have only recently begun…. The primary effects of HABs on human beings and animals occur through exposure to the toxins produced by the HAB-forming organisms.”

Discussing “Algal Toxins” in Water and Sanitation Related Diseases… Fleming and Backer et al write, “Marine and freshwater algae comprise an ancient microbial assemblage that includes dinoflagellates, diatoms, and cyanobacteria [toxic cyanobacteria is discussed in another chapter in this book]. Although ubiquitously present, periodically these organisms grow exuberantly to form blooms. The blooms are considered harmful …when they pose risks to the local ecology, such as from oxygen depletion, nutrient depletion, or light deprivation. HABs may also be associated with adverse health effects in wildlife, domestic animals, and people through the physical factors mentioned previously or because they produce potent toxins...there is evidence that HABs are occurring more frequently and more extensively than in the past.”

Both in that book and in Human-Animal Medicine, Tables are used to describe toxin, organism, exposure route or transvector, and health effects. For example, animals and humans suffer adverse health effects of toxin saxitoxin. For animals these include “incoordination, recumbency, death by respiratory failure. For humans, they include “paresthesia and numbness of lips and mouth extending to face, neck, and extremities…motor weakness…incoordination, respiratory and muscular paralysis.”

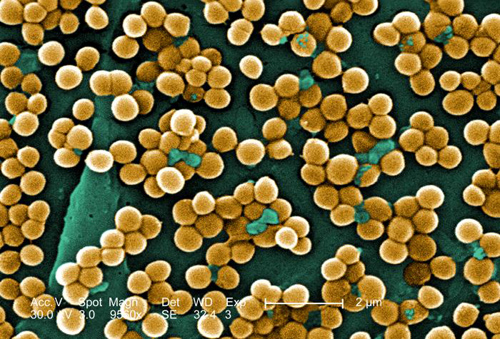

MRSA: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, e.g., bloodstream, pneumonia, bone infections…: Human-Animal Medicine states: "The risk of transmission between humans and other animals may vary by species and type of MRSA. One study found evidence of MRSA transmission between dogs and veterinary workers. Equine-human zoonotic transmission has been clearly established. The mode of transmission in the community is thought to be primarily by hands that have become contaminated by contact with colonized or infected body sites of other individuals or fomites contaminated with body fluids containing MRSA. Other factors contributing to transmission include skin-to-skin contact, crowded conditions, and poor hygiene. Risk factors for acquisition of MRSA are likely to include certain antimicrobial use in veterinary medicine. This 2005 scanning electron micrograph (SEM) depicted numerous clumps of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, commonly referred to by the acronym, MRSA; Magnified 9560x. Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA). Image by CDC/ Janice Haney Carr/ Jeff Hageman, M.H.S.

MRSA: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, e.g., bloodstream, pneumonia, bone infections…: Human-Animal Medicine states: "The risk of transmission between humans and other animals may vary by species and type of MRSA. One study found evidence of MRSA transmission between dogs and veterinary workers. Equine-human zoonotic transmission has been clearly established. The mode of transmission in the community is thought to be primarily by hands that have become contaminated by contact with colonized or infected body sites of other individuals or fomites contaminated with body fluids containing MRSA. Other factors contributing to transmission include skin-to-skin contact, crowded conditions, and poor hygiene. Risk factors for acquisition of MRSA are likely to include certain antimicrobial use in veterinary medicine. This 2005 scanning electron micrograph (SEM) depicted numerous clumps of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, commonly referred to by the acronym, MRSA; Magnified 9560x. Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA). Image by CDC/ Janice Haney Carr/ Jeff Hageman, M.H.S.

Human-Animal Medicine lays the foundation for appreciation of the importance of, and calls for, better communication between veterinarians and local public health officials to protect both the public and animals. Fleming and Backer use the example of bloom detection in 1984 in Montana. “…people who had been swimming in a lake contacted the local health department to report dead cattle in and near the lake and to ask about their own risks of becoming ill.” The investigation found that the wind had concentrated a toxin-producing bloom of several cyanobacteria … against the shore of the lake where the cattle had been drinking. Because people had been swimming in another part of the lake, their exposure was limited and no bloom-associated human illnesses were reported.”

This and other examples of relationships between human and animal health are effectively presented throughout this book. These relationships are, according to Fleming and Backer “…becoming increasingly complex and include biological, chemical, physical and social factors.”

Panama Canal: Two aspects of public health concern are in evidence in this photo of the locks at the Pacific Ocean end of the: Panama Canal: the current and the historical. Vessels carry goods back and forth through the canal from all parts of the globe. Nearly 14,000 ships a year travel through the canal. The tonnage of the goods they carry is almost 195 million. Historically, the narrow 40 mile isthmus attracted the interest of developers in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Although a formidable engineering challenge, the terrain was less daunting than the disease-carrying mosquitoes of the region. Under the leadership of Colonel William C. Gorgas, U.S. Army, M.D., public health officials instituted sanitation measures that eliminated the yellow fever- and malaria-carrying mosquitoes, which made building the canal possible. Currently the Canal Zone is a tourist destination. It is important for all travelers to be aware of the potential health hazards of both foreign and domestic travel. To address health issues associated with travel, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers tips for U.S. travelers on how to avoid illness while away from home. A greater problem is that of globalization’s effect on infectious disease transmission. Health problems can no longer be thought of as “local.” CDC’s “PulseNet” is one effort used to monitor laboratory gel patterns to quickly identify dispersed domestic and international outbreaks of infectious disease. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA). Image by CDC/ Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.

Panama Canal: Two aspects of public health concern are in evidence in this photo of the locks at the Pacific Ocean end of the: Panama Canal: the current and the historical. Vessels carry goods back and forth through the canal from all parts of the globe. Nearly 14,000 ships a year travel through the canal. The tonnage of the goods they carry is almost 195 million. Historically, the narrow 40 mile isthmus attracted the interest of developers in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Although a formidable engineering challenge, the terrain was less daunting than the disease-carrying mosquitoes of the region. Under the leadership of Colonel William C. Gorgas, U.S. Army, M.D., public health officials instituted sanitation measures that eliminated the yellow fever- and malaria-carrying mosquitoes, which made building the canal possible. Currently the Canal Zone is a tourist destination. It is important for all travelers to be aware of the potential health hazards of both foreign and domestic travel. To address health issues associated with travel, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers tips for U.S. travelers on how to avoid illness while away from home. A greater problem is that of globalization’s effect on infectious disease transmission. Health problems can no longer be thought of as “local.” CDC’s “PulseNet” is one effort used to monitor laboratory gel patterns to quickly identify dispersed domestic and international outbreaks of infectious disease. Caption and Image from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, Atlanta, GA). Image by CDC/ Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.

While over the years there have been collaborations between animal and human health providers, “…it was in 1960’s that a veterinarian, Dr. Calvin W. Schwabe, a parasitologist and veterinary epidemiologist coined the term One Medicine in his textbook, Veterinary Medicine and Human Health,” and called for collaboration to combat zoonotic diseases.

Among the number of organizations and collaborations, which have formed in recent years to expand upon Schwabe’s model, “…the American Medical Association (AMA) and American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) began collaborative efforts on a One Health Initiative (also referred to as One Medicine, One-Medicine-One Health, and One World One Medicine One Health).”

A “consultation document, ‘Contributing to One World, One Health: Strategic Framework for Reducing Risks of Infectious Diseases at the Animal-Human-Ecosystem Interface,’ was produced by the Food and Agriculture Organizations of the United Nations (FAO), World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations System Influenza Coordination, United Nations Children’s Emergency Funds UNICEF), and the World Bank and published in 2008 (see http://www.oie.int/downld/AVIAN%20INFLUENZA/OWOH/OWOH_14Oct08.pdf).

Human-Animal Medicine “provides numerous practical suggestions for helping [human and animal health professionals] retool and implement One Health concepts into their daily practice routines, which could enhance the preventive and therapeutic care they provide and lead to greater convergence between the disciplines,” the authors write.

Even those less familiar with the medical terminology used can find this book is a valuable resource. It is heavily illustrated with often startlingly vivid photographs comparing human and animal manifestations of diseases. Among them are contrasting images of Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) soft tissue infection on a human with a dog with severe crusting erosive dermatitis on its face suffering from a secondary MRSA infection “possibly obtained from the owner, who worked in human health care industry.”

This Human-Animal Medicine book, the One Health Initiative, and related endeavors can advance the synergy achievable with interdisciplinary collaborations and communications in all aspects of health care for humans, animals and the environment.

As is so well expressed on the One Health Initiative Web site, such synergy will “advance health care for the 21st century and beyond by accelerating biomedical research discoveries, enhancing public health efficacy, expeditiously expanding the scientific knowledge base, and improving medical education and clinical care.

Review by Janine M. H. Selendy, Founder, Chairman, President and Publisher, Horizon International, 6 June 2013

Additions of March 29,2021:

See:

The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE): https://www.oie.int/

See Infographic available at:

https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Media_Center/img/Infographies/A4-EN-WEB.pdf

Human-Animal Medicine: Clinical Approaches to Zoonoses, Toxicants and Other Shared Health Risks is available from Saunders: Human-Animal Medicine - ISBN: 978-1-4160-6837-2 - Elsevier Health.

About the authors:

Peter M. Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, is Associate Professor of Medicine and Director of Clinical Services Yale Occupational and Environmental Medicine Program, Yale University School of Medicine

Lisa A. Conti, DVM, MPH, DACVPM, CEHP, is the current Deputy Commissioner and Chief Science Officer at Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Drs. Rabinowitz and Conti are among the founders of the One Health Initiative (OHI). Dr. Peter M. Rabinowitz serves on the Advisory Board and Dr. Lisa A. Conti is a member of the OHI team along with Laura H. Kahn, MD, MPH, MPP, Bruce Kaplan, DVM, and Jack Woodall, PhD.

The Human Animal Medicine Project at Yale School of Medicine, for which Dr. Peter Rabinowitz is Executive Director, and on whose research team Dr. Conti serves, explores clinical connections between human and animal medicine using a comparative "One Health" approach. These connections include:

· Zoonotic infectious diseases at the human-animal interface

· Animals as “sentinels” of environmental health hazards presented in its

Canary Database available at http://www.canarydatabase.org

· Clinical collaboration between human health care providers and veterinarians

Notes, Related Coverage and Web Sites:

· Horizon International Endorsement of The One Health Initiative, excerpts:

“As is so well expressed on the OHI Web site, such synergy will ‘advance health care for the 21st century and beyond by accelerating biomedical research discoveries, enhancing public health efficacy, expeditiously expanding the scientific knowledge base, and improving medical education and clinical care,” wrote Janine M. H. Selendy, in her endorsement on behalf of Horizon International.

Horizon International has joined more than 700 prominent scientists, physicians and veterinarians worldwide who have endorsed the initiative and to be part of the One Health Initiative “movement to forge co-equal, all inclusive collaborations between physicians, osteopaths, veterinarians, dentists, nurses and other scientific-health and environmentally related disciplines.”

· One Health Newsletter (OHNL) features articles on “Nipah virus, swine flu, SARS, bird flu, and the novel coronavirus are examples of diseases at the interface of humans, bats, birds, and pigs.”

· Practicing "One Health" for the Human Health Clinician (Physicians, Osteopaths, Physician Associates, Nurse Practitioners, Other Human Health Care Providers) - April 2012:

English and Spanish language versions (respectively)

:: View PDF - English Version ::

:: View PDF - Spanish Version ::

· Human Disease Leptospirosis Identified in the Banded Mongoose in Africa, published on May 20, 2013, on the Horizon International Solutions Site at http://www.solutions-site.org/node/892.

· Actions Combating Drug Resistance, published on March 23, 2112, on the Horizon International Solutions Site at http://www.solutions-site.org/node/675

* A ‘‘One Health’’ Approach to Address Emerging Zoonoses: The HALI Project in Tanzania

Credits:

Citation: Mazet JAK, Clifford DL, Coppolillo PB, Deolalikar AB, Erickson JD, et al. (2009) A ‘‘One Health’’ Approach to Address Emerging Zoonoses: The HALI Project in Tanzania. PLoS Med 6(12): e1000190.doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000190 Published December 15, 2009

Copyright: _ 2009 Mazet et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References cited:

1. World Health Organization (2009) Data and statistics: Causes of death. Geneva: World Health Organization, Available: http://www.who.int/research/en/. Accessed 24 April 2009.

2. World Health Organization (2006) The control of neglected zoonotic diseases: A route to poverty alleviation. Report of a joint WHO/DFID-AHP meeting, 20 and 21 September 2005, WHO Headquarters, Geneva, with the participation of FAO and OIE. Available: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/9789241594301_eng.pdf

3. Taylor LH, Latham SM, Woolhouse MEJ (2001) Risk factors for human disease emergence. Phil Trans Royal Society B 356: 983–989.

4. Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, et al. (2008) Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451: 990–993. doi:10.1038/nature06536.

5. Moran M, Guzman J, Ropars A-L, McDonald A, Jameson N, et al. (2009) Neglected disease research and development: How much are we really spending? PLoS Med 6: e1000030. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000030.

6. Clifford D, Kazwala R, Coppolillo P, Mazet J (2008) Evaluating and managing zoonotic disease risk in rural Tanzania. Davis (California): Global Livestock Collaborative Research Support Program Research Brief 08-01-HALI. Available: http://glcrsp.ucdavis.edu/publications/HALI/ 08-01-HALI.pdf. Accessed 24 April 2009.

7. Coppolillo P, Dickman A (2007) Livelihoods and protected areas in the Ruaha Landscape: A preliminary review. In: Redford KH, Fearn E, eds. Protected areas and human livelihoods. New York: Wildlife Conservation Society, Working Paper No. 32. Available: http://www.ecoagriculture.org/documents/files/doc_40.pdf Accessed 17 November 2009.

8. Ogelthorpe J, Gelman N (2007) HIV/AIDS and the environment: Impacts of AIDS and ways to reduce them. A fact sheet for the conservation community. Washington (D. C.): World Wildlife Fund, Available: http://www.worldwildlife.org/what/communityaction/people/phe/WWFBinaryitem7051.pdf. Accessed 24 April 2009.

9. Newark WD (2008) Isolation of African protected areas. Front Ecol Environ 6: 321–328.

10. Wittemyer G, Elsen P, Bean WT, Coleman A, Burton O, et al. (2008) Accelerated human population growth at protected areas edges. Science 321: 123–126.

11. United Nations (2008) Contributing to One World, One Health: A strategic framework for reducing risk of infectious diseases at the animal-human-ecosystem interface. FAO/OIE/WHO/UNICEF/UNSIC/World Bank. Available: http://un-influenza.org/files/OWOH_14Oct08.pdf. Accessed 24 April 2009.

Book CoverBook Cover This article is presented as part of the Supplementary Material that accompanies the book Water and Sanitation Related Diseases and the Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures, a Wiley-Blackwell publication in collaboration with Horizon International, written by 59 experts. Janine M. H. Selendy, Horizon International Founder, Chairman, President and Publisher, is Editor.

Book CoverBook Cover This article is presented as part of the Supplementary Material that accompanies the book Water and Sanitation Related Diseases and the Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures, a Wiley-Blackwell publication in collaboration with Horizon International, written by 59 experts. Janine M. H. Selendy, Horizon International Founder, Chairman, President and Publisher, is Editor.

The book’s 4 hours of multimedia DVDs are included with an abundance of multidisciplinary resources, covering diverse topics from anthropology to economics to global health are being distributed free of charge by the Global Development And Environment Institute (GDAE) at Tufts University.

These will be sent to thousands of libraries, organizations, and institutions in 138 less-wealthy countries and will be invaluable additions to library materials for use in classrooms and communities, by researchers and government decision-makers.

Map of countriesMap of countries

Map of countriesMap of countries

As of 17 September 2013, these resources have been made available in over 1,200 entities across 60 countries.

Read more: PDF Version is available at http://solutions-site.org/press/release1july2013.pdf

Search

Latest articles

Agriculture

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Air Pollution

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Biodiversity

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Desertification

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- UN Food Systems Summit Receives Over 1,200 Ideas to Help Meet Sustainable Development Goals

Endangered Species

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

- Coral Research in Palau offers a “Glimmer of Hope”

Energy

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Wildlife Preservation in Southeast Nova Scotia

Exhibits

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Coral Reefs

Forests

- NASA Satellites Reveal Major Shifts in Global Freshwater Updated June 2020

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Global Climate Change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

Global Health

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- More than 400 schoolgirls, family and teachers rescued from Afghanistan by small coalition

Industry

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Natural Disaster Relief

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

News and Special Reports

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

Oceans, Coral Reefs

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Pollution

- Zakaria Ouedraogo of Burkina Faso Produces Film “Nzoue Fiyen: Water Not Drinkable”

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Population

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Public Health

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Rivers

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Toxic Chemicals

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Actions to Prevent Polluted Drinking Water in the United States

Transportation

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Urbanization Provides Opportunities for Transition to a Green Economy, Says New Report

Waste Management

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water and Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution